Living Income Differential, What’s that?

In this second article of the Cocoa Market Series, we focus on the backbone of the cocoa industry: the farmers and their families. Farmers who work with tree crops like cocoa face high sunk costs when they begin their investment. Switching to different crops is not a viable option if market prices suddenly drop. This price volatility and the persistently low market prices have attracted the attention of governments, NGOs, and international organizations. These economic challenges threaten the livelihoods of up to 6 million cocoa farming families who rely solely on cocoa sales for their income.

In response to these challenges, the Ghanaian and Ivorian governments have recently embraced the “Living Income Differential” (LID) household concept. This concept aims to ensure that farmers earn enough to achieve a decent standard of living for their households. This includes adequate food, decent housing, and other essential needs such as education, clothing, medicine, and transportation, as well as savings for unexpected events like fire or medical emergencies.

While the LID is a somewhat subjective measure, as it depends on various contextual factors, it has been implemented to alleviate the high poverty rates in rural Ghana and Ivory Coast. The policy introduces an additional USD 400 per ton of cocoa on top of the floor price paid by cocoa buyers during the 2020/21 crop season. This initiative aims to provide a more stable and sustainable income for cocoa farmers, helping to improve their quality of life and reduce poverty in cocoa-producing regions.

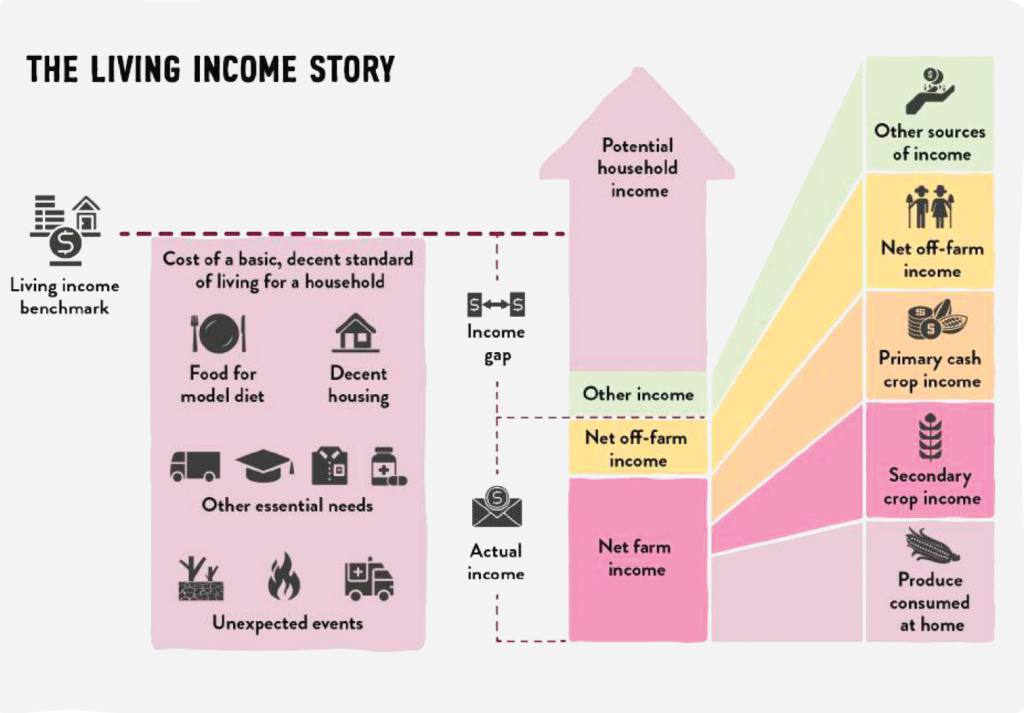

The Living Income Differential (LID) aims to bridge the gap between the actual income earned by farmers and the Living Income Benchmark, representing the ideal earnings needed for a decent standard of living. This gap, known as the income gap, highlights the shortfall farmers must overcome to achieve a sustainable livelihood.

According to a study conducted by Wageningen University & Research and Mondelez in 2019, the average daily income per person in Ghana and Ivory Coast was $1.42 USD and $1.23 USD, respectively. In contrast, the Living Income Benchmark suggests that cocoa farmers should be earning approximately $2.55 USD per day in Ivory Coast and $2.08 USD per day in Ghana. This significant disparity underscores the importance of initiatives like the LID in supporting cocoa farmers and ensuring their economic well-being. In macroeconomic terms, the study indicates that raising 30-40% of farming households to a living income level would require a payment of USD 5.21 million based on 2018 data. This amount represents nearly 10% of the combined GDP of Ivory Coast and Ghana in 2018 and is almost double the current export revenues of both countries, which are estimated at USD 5.31 billion. To elevate approximately 75% of households to a living income, an additional annual payment of USD 10 billion would be necessary.

I believe that the concept of a living income is crucial for addressing human rights, sustainability, and poverty alleviation. However, simply increasing prices may not be the ideal solution, as it could lead to supply-demand imbalances. Historically, higher prices have sometimes resulted in cocoa oversupply, which subsequently drove international prices down. Alleviating poverty is a complex and multidimensional challenge that requires holistic thinking. For instance, higher prices might increase farmers’ dependency on cash crops. Therefore, the solution may also lie in helping farmers develop value-added activities across the supply chain, such as cocoa processing. Additionally, promoting agroforestry farming, where multiple crops are grown and sold, investing in machinery and fertilizers, and encouraging family members to seek employment in other sectors like tourism can diversify income sources and enhance economic resilience. Moreover, governments in cocoa-producing countries must improve governance and transparency regarding the reinvestment of cocoa tax earnings. Developing key sectors such as road infrastructure, personal banking, and microfinance can significantly impact farmers’ lives and reduce their business costs.

In the coming section, I will discuss how the Ghanaian and the Ivorian governments have worked togethers price stabilization for farmers and provide recommendations on how to go forward.

Cocoa Pricing Policy from Country Perspective

The Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD), operating under the Ministry of Finance, is responsible for regulating the cocoa sector, including setting export and farm-gate prices. Established over 70 years ago, COCOBOD has experienced periods of both high regulation and liberalization. In Ivory Coast, following a decade of full liberalization partly due to civil war, the Conseil du Café-Cacao (CCC) was introduced in 2011 to govern the cocoa sector.

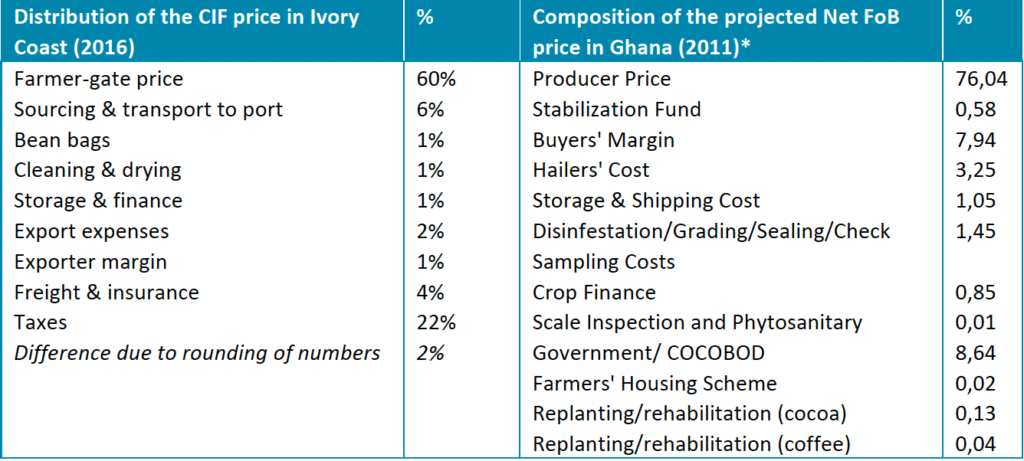

At the beginning of the season, the Ghanaian government, through COCOBOD and related agencies, aims to sell forward contracts and futures for about 70% of the anticipated harvest. In contrast, the Ivorian Cocoa-Coffee Council uses an export auction system where exporters must sell cocoa to international buyers. The export price of cocoa futures determines the farm-gate price that farmers receive during the season. While this system does not fully protect farmers from low market prices, it provides some stability by locking in prices in advance. In Ghana, the farm-gate price is set at approximately 70% of the FOB (Free on Board) export price, whereas in Ivory Coast, it is around 60% of the CIF (Cost, Insurance, and Freight) export price. These prices are enforced by COCOBOD and the CCC, respectively.

Note: CIF and FOB are international trade terms that delineate the responsibilities of sellers and buyers. Under CIF, the seller covers the total cost of goods, freight, and insurance, while FOB requires the seller only to cover the cost of loading the goods onto the vessel.

Farmers receive a specific percentage of the export price, and so do all intermediaries in the production supply chain, including transportation, storage, duties, insurance, bean cleaning, and drying. These margins are set either as a fixed price or as a percentage of the export price. Since intermediaries cannot compete on price, they focus on providing better services to farmers, such as pre-financing, quick payments, or access to farming inputs like fertilizers. Many intermediaries have grown large to handle substantial volumes and achieve economies of scale, which helps them remain profitable.

Premium cocoa beans can be kept separate from bulk cocoa, allowing farmers to deal directly with buyers to improve traceability and secure better prices. These premium payments often cover deficits that would otherwise prevent farmers from investing in better land management or basic farming technology.

Research shows a positive correlation between market regulation and cocoa quality. This is supported by data indicating that Ghanaian cocoa has historically traded at a premium of 7-10% above the average world market price. In 2012, the Ivorian government introduced reforms that also improved cocoa quality standards, reducing the competitive advantage of Ghanaian cocoa. From 2007 to 2016, the nominal farm-gate price in Ghana increased sevenfold under a more regulated market tied to FOB prices.

Regulated cocoa markets in Ghana and Ivory Coast use “stabilization funds” managed by government entities to stabilize farmers’ incomes. When market prices exceed the set price for the season, the excess is injected into the fund for reinvestment during low-price periods. Conversely, when the set price is higher than the market price, the government uses the fund to pay the difference to farmers and intermediaries, thereby fulfilling its promise. The table below illustrates how set prices are allocated to each cost component, showing that in both Ivory Coast and Ghana, the producer price or farm-gate price constitutes the largest component, followed by taxes.

While these developments are beneficial for farmers and poverty reduction, challenges in policy-making remain. Farmers are highly vulnerable to currency risk and devaluation, with the depreciation of the Ghanaian cedi against the USD leading to them receiving up to 70% less than the FOB price. As farmers sell in Ghanaian cedi, their purchasing power diminishes when importing goods and services, which become increasingly expensive. Additionally, farm-gate prices set by the Producer Price Review Committee prices have been used as political tools to win elections, with promises of artificially high prices leading to further currency devaluation or the misuse of stabilization funds to meet electoral promises.

According to Aidenvironment Research (2018), the primary challenge in sector-led models is maintaining transparency and accountability. In Ivory Coast, the auction system for cocoa prices needs greater transparency to clearly show how prices and volumes are determined. Additionally, there must be more detailed reporting on how taxes collected from export sales are reinvested to benefit farmers. This includes assessing the impact of these investments on farmers’ living standards, sustainability practices, and economic diversification. Enhanced checks and balances are necessary to improve the governance of price-setting and tax investment bodies. This includes ensuring that price stabilization funds are managed independently from any political party and remain free from political interference.

Key Measures of the Ghanaian Government in 2024

The depreciation of the Ghanaian cedi against the USD since 2022 has adversely affected consumers’ purchasing power. In response, the Ghanaian government has increased the farmgate price for cocoa farmers by approximately 58%, setting it at GH¢33,120 per ton for the 2023/24 crop season. This increase aims to deter farmers from smuggling cocoa to neighboring countries like Ivory Coast, where cocoa is sold in CFA Francs, which are pegged to the USD and EUR, providing greater stability for farmers.

Additionally, the Ghanaian government has decided to open the cocoa trading season one month earlier this year. This decision is intended to allow farmers to benefit from higher farmgate prices and to compensate for the supply chain disruptions experienced this year. These disruptions include the Cocoa Swollen Shoot Virus Disease (CSSVD), which led to a 25% reduction in the harvest compared to original projections and caused delays in fulfilling 44,000 metric tons of cocoa bean supply contracts. Consequently, Ghana’s cocoa export expectations have been revised to 650,000 metric tons, down from the initially projected 850,000 metric tons.

What measures should be taken in your view if you were in charge of the COCOBOD to further help farmers? Let’s discuss.

Bibliography

- LinkedIn Article: Three Mountains Cocoa. (n.d.). September Crop Seasonal Shift for Ghana’s Farmers. Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/september-crop-seasonal-shift-ghanas-farmers-threemountainscocoa/

- Report: Aidenvironment and Sustainable Food Lab. (2018, October). Pricing mechanisms in the cocoa sector: Options to reduce price volatility and promote farmer value capture. Originally prepared February 2018. Supported by GIZ and ISEAL Alliance, IBNACLOAMNEC ICNHGA TLHLEEN LGIEVING.

- Research Paper: Waarts, Y., & Kiewisch, M. (2021, November). Towards a multi-actor approach to achieving a living income for cocoa farmers. Wageningen University & Research and Mondelēz International Cocoa Life.