Mexico City is sinking each year, and not just by a few inches as one might think. In reality, it’s sinking by about 50 centimeters, or 20 inches, annually. This ongoing subsidence raises questions: Why is this happening, and why should we care?

My uncle explained that the city is built on a unique mix of volcanic rocks and sediments.

Historically, water naturally flowed upwards through this terrain. In its past life as Tenochtitlán, the city boasted a sophisticated network of waterways for transporting people and goods.

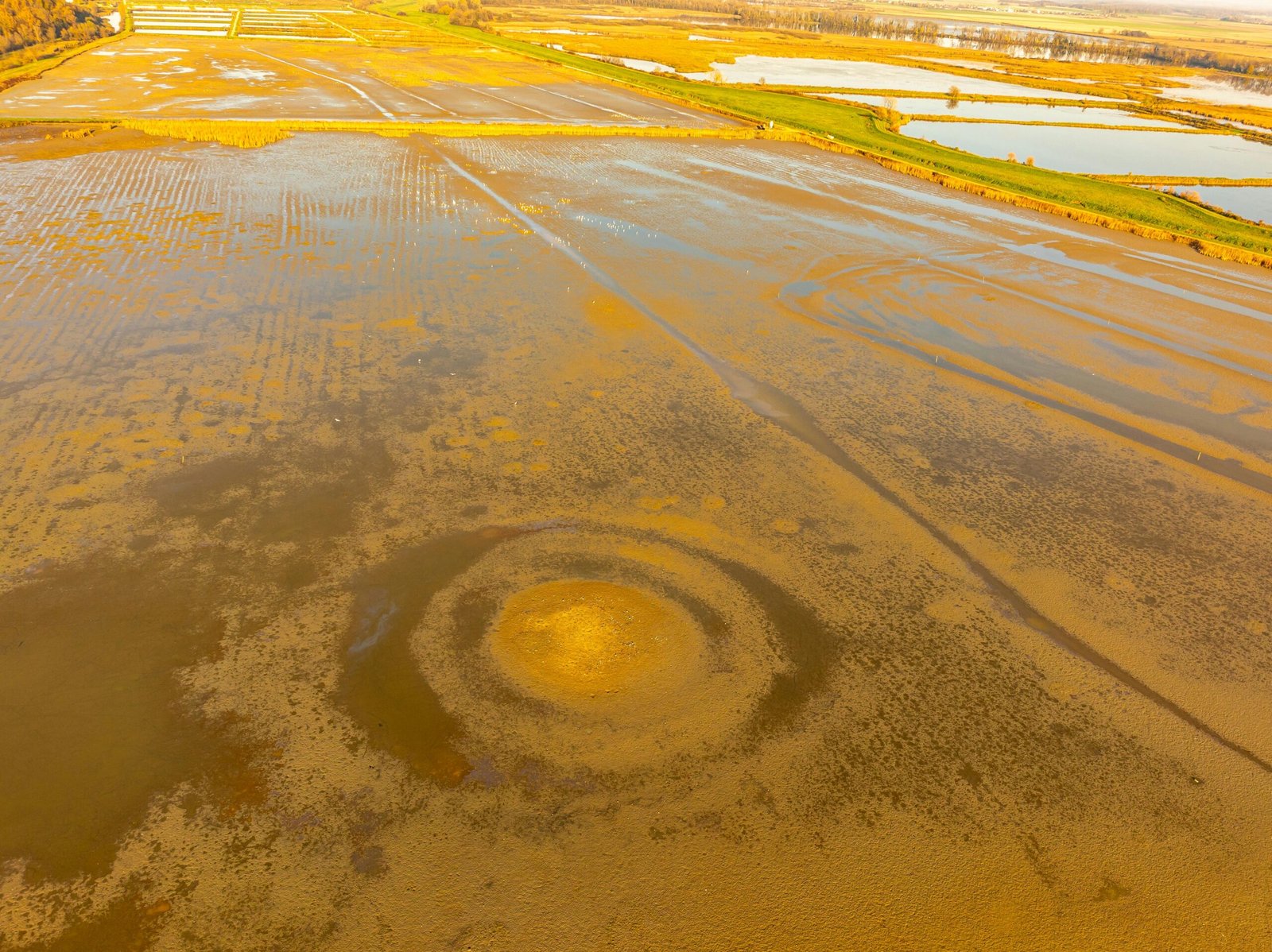

Today, as one of the largest cities in the Americas, Mexico City relies heavily on aquifers for its water supply. The city is sinking because it is situated on what once was Lake Texcoco, a “clay-rich lake bed” where mineral grains are compressed, causing the ground to shrink.

If you’ve visited Mexico City, you’ve likely noticed the numerous holes, or “hoyos,” and the fractured water lines that lead to contamination and water loss. For a summary of the current water crisis, visit: https://lnkd.in/gkj58u4d

However, this is not an isolated issue. Major urban centers across America and Asia also depend on aquifers for water. Aquifers account for 97% of Earth’s liquid freshwater reserves. For instance, a massive aquifer in China’s Huang-Huai-Hai plain supplies water to over 160 million people.

The pressing concern is that we are depleting these aquifers faster than they can naturally recharge. Agriculture accounts for the largest portion of global water withdrawals. In low and middle-income countries, the percentage of freshwater used for agriculture is typically highest. However, there are exceptions, such as in California, where 80% of freshwater withdrawals support agricultural activities.

Exporting water-intensive crops to countries with abundant water resources underscores a misallocation of resources. For instance, Mexico ranks seventh in the world for extracting more water from aquifers annually than is naturally replenished, with 23% of these water-intensive crops being exported. In the U.S., this figure rises to 42.5%. What do these statistics tell us?

1. Firstly, public water policy should evaluate whether governments are sending the right price signals for irrigated water. Are subsidies encouraging investments in water-intensive crops in regions facing water scarcity? Are we incentivizing the cultivation of crops suited to our local resources?

2. Secondly, why are we exporting water-intensive crops to countries with more abundant water supplies than our own? This calls for reflection on our current practices.

#SustainableWater hashtag#WaterManagement hashtag#WaterEconomics

Bibliography

- Barbier, E. (2019). The water paradox: Overcoming the global crisis in water management. Yale University Press.

- Eos. (n.d.). The looming crisis of sinking ground in Mexico City. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://eos.org/research-spotlights/the-looming-crisis-of-sinking-ground-in-mexico-city

- U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). (n.d.). Where is Earth’s water? Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://www.usgs.gov/special-topics/water-science-school/science/where-earths-water

- Dalin, C., Wada, Y., Kastner, T., & Puma, M. J. (2017). Groundwater depletion embedded in international food trade. Nature, 543(7647), 700–704. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21403