Global Environment Facility Background

The Global Environment Facility (GEF) was established in October 1991 as a pilot program by the World Bank with the mission of protecting the global environment. Its goal was to promote sustainable development by providing grants, concessions, and venture capital funding for projects aligned with environmental objectives. In 1994, the GEF became an independent institution but continued to use the World Bank as its Trustee.

The primary objectives of the GEF include funding projects that benefit the environment in the following focal areas:

- Biodiversity;

- Climate Change;

- International Waters;

- Land Degradation;

- Reduction of Chemicals and Waste;

The GEF is funded by contributions from participating donor countries, which are managed through several trust funds administered by the World Bank. An independent Secretariat, also located at the World Bank, oversees the disbursement of these funds. The Trustee’s main responsibilities are to:

- Mobilize donor-funded resources for the GEF;

- Organize replenishment meetings with donor governments—such as the June 2022 meeting where 29 donor governments pledged USD 5.33 billion for the next four years;

- Prepare financial reports and statements on the efficacy of the funds in supporting development and sustainable projects, and;

- Regularly monitor the budgetary and project funds.

The Global Environment Facility (GEF) operates with a structured governance and organizational framework. It includes 182 member governments, overseen by the GEF Council, which consists of 32 members. Every four years, the GEF Assembly convenes, representing all member countries.

The GEF Secretariat, led by the CEO, administers the fund. Operational responsibilities are handled by GEF agencies, which are accountable to the Council for their project activities.

The Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel (STAP) offers scientific and technical advice on policies, operational strategies, programs, and projects. This panel is composed of six internationally recognized experts in key areas of the GEF’s work, supported by a global network of experts and institutions.

The Independent Evaluation Office, led by a Director appointed by the Council, conducts independent evaluations of the GEF’s impact and effectiveness. It coordinates a team of specialized evaluators and collaborates with the Secretariat and GEF Agencies to share lessons learned and best practices. The evaluations typically focus on focal areas, institutional issues, or cross-cutting themes.

The Global Environment Facility (GEF) provides funding to support government projects and programs, with governments selecting the appropriate executing agencies. When seeking GEF funding, several key considerations include eligibility, implementing agencies, and project type. Eligible projects must originate from qualifying countries, align with both national and GEF priorities, and involve public participation. Funding covers only the incremental costs necessary to achieve global environmental benefits.

The GEF collaborates with 18 partner agencies, such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the African Development Bank (AfDB), and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), as chosen by the Operational Focal Point to develop and implement projects. Funding modalities include full-sized projects, medium-sized projects, enabling activities, and programmatic approaches, each tailored for specific objectives and requiring distinct templates. The Operational Focal Point reviews project ideas for eligibility.

But how is the GEF actually guided? How does it make long-term decisions? The GEF serves as the financial mechanism for five international environmental conventions:

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

- Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs)

- United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD)

- Minamata Convention on Mercury

These conventions are fundamental to global environmental governance, and I will briefly summarize their relevance.

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) main purposes are to protect biological diversity across the globe and use the Earth’s resources and components in a sustainable manner such that equitable access is given. This includes preventing biodiversity loss, ensuring fair use and access to the treasures that biodiversity provides to humans. CBD was agreed in 1992 at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and it came into force in December 1993 with 168 nations signing up in the first year. These are elaborated in 42 articles and implementation is discussed every two years at the Convention of the Parties (COP). The most recent one was held in Canada in 2022, known as COP15. During the meeting, clear targets to tackle overexploitation, pollution and unsustainable agricultural practices and a plan to safeguard the rights of indigenous peoples. Additionally, there was a focus on financing biodiversity and aligning financial flows to support sustainable investments while moving away from environmentally harmful practices.

The Cartagena and Nagoya Protocols are vital international treaties under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The Cartagena Protocol, effective since 2003, focuses on safeguarding human health and biodiversity from genetically modified organisms (GMOs). This includes rules for managing any damage that might arise from GMO use. In contrast, the Nagoya Protocol, enacted in 2014, addresses benefit sharing from the use of genetic resources. It ensures that benefits from bioprospecting—like drug production—are shared with the country of origin. Despite challenges in terms of bureaucracy and ambiguous definitions, these protocols aim to promote equity and sustainability. They also recognize the rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) in benefiting from genetic resources and traditional knowledge.

Biodiversity continues to decrease at alarming rates, with reports indicating that animal populations have dropped by over two-thirds since 1970 and more than one million species are at risk of extinction, according to the WWF and the UN body IPBES. CBD aims at tackling the problem by establishing a Global Taxonomy Initiative (GTI), which aims at mapping all species across the world and building digital knowledge banks to foster collaboration and agreement of the endangered species, their ecosystem importance and prevent destruction by bringing awareness. Another goal of the CBD is to bridge the technical and knowledge gap between developed and developing countries such that funding gaps decrease and science work is translated to practical matters that foster biodiversity preservation. Policy translation and practical execution would increase CBD’s exposure to local communities and help in getting closer to the areas in need.

COP meetings serve to establish goals related to biodiversity conservation. Prior to COP15, there were specific numerical goals assigned to each member country such as increasing the area of the natural ecosystem by 15%. However, biodiversity targets are not legally binding which leads to difficulty in achieving them. None of the 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets were fully met. Significant discussions at COP15 also focused on Digital Sequence Information (DSI), covering genetic sequences amid unresolved legal and benefit-sharing issues. Countries agreed to enhance the sharing of DSI benefits, but specific implementations remain undecided. Future COPs may bring further changes as new priorities emerge.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

The UNFCCC entered into force on 21 March 1994, whose main goal is to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations “at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic (human induced) interference with the climate system.” It states that “such a level should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened, and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.”

The Global Environment Facility (GEF) framework emphasizes the responsibility of developed countries to lead the way in addressing climate change. As these industrialized nations have historically contributed the most to greenhouse gas emissions, they are tasked with taking significant action to reduce emissions within their territories. These nations, identified as Annex I countries and members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), include twelve nations with “economies in transition” from Central and Eastern Europe. By the year 2000, Annex I countries were expected to bring their emissions down to 1990 levels—a target many have actively pursued and successfully achieved in some cases, driven by initiatives such as the Kyoto Protocol.

In addition, the GEF directs new funding towards climate change initiatives in developing countries, with industrialized countries agreeing to financially support these efforts. This support is meant to go above and beyond their existing aid commitments, facilitated through a system of grants and loans managed by the GEF. These countries also pledge to share technology with less-developed nations. Reporting mechanisms are in place to monitor progress, requiring Annex I countries to provide regular updates on their climate policies and greenhouse gas inventories. Non-Annex I Parties, or developing countries, report on their climate actions less frequently and in a more general manner, contingent on receiving funding for report preparation, especially for the Least Developed Countries.

Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs)

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) emerged during the post-World War II industrial boom, bringing with them both benefits and unforeseen consequences. Initially, many of these synthetic chemicals were hailed for their roles in pest and disease control, crop production, and industrial applications. Among the most well-known POPs are PCBs, DDT, and dioxins. Despite their usefulness, these substances have had detrimental impacts on human health and the environment.

POPs can be categorized into intentionally produced chemicals, such as PCBs and DDT, and unintentionally produced chemicals, like dioxins. PCBs were widely employed in industrial applications, including electrical transformers, hydraulic fluids, and as additives in paints and lubricants. DDT was renowned for its effectiveness in controlling malaria-carrying mosquitoes and protecting agricultural crops, especially cotton. However, these chemicals also led to severe environmental contamination and human exposure to harmful substances.

The global spread of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) underscores their transboundary nature. POPs can travel vast distances through various environmental media—air, water, and even migratory species. They evaporate from surfaces, attach to airborne particles, and return to the Earth via precipitation, thus spreading their toxic effects over long ranges. This widespread contamination was notably highlighted by the discovery of POPs in the Arctic, far from any known sources.

The Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, adopted in 2001 and effective since 2004, was significantly driven by these findings. Managed by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), the Convention’s Conference of the Parties (COP) oversees its implementation. The Convention mandates parties to eliminate or reduce POPs, which can cause severe health issues like cancer and diminished intelligence. Parties are responsible for eliminating or restricting the production and use of POPs, conducting research, identifying contaminated areas, and providing financial support for these initiatives.

While POPs were initially valued for their industrial and agricultural benefits, their long-term environmental and health impacts have proven detrimental. The Global Environment Facility (GEF) plays a crucial role in supporting such efforts, aiming to protect ecosystems and human health from the pervasive threat of POPs.

UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD)

Desertification refers to areas with low or variable rainfall and is closely linked to land degradation caused by high population growth, urbanization, large-scale deforestation, ranching, mining, and agricultural land clearing practices. It is anticipated that desertification will displace around 50 million people by 2030 due to high temperatures, resource scarcity, and ecosystem damage. Additionally, droughts are likely to become more frequent and intense.

This significant environmental issue impacts regions globally, with over 60% of Central Asia at risk. Rising temperatures in countries like China, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan have exacerbated the problem, pushing desert climates further into northern Uzbekistan, southern Kazakhstan, and the Junggar Basin in China. In mountainous areas such as the Tian Shan region, warming and wetter conditions are causing glaciers to retreat, leading to water shortages that affect local populations and agriculture.

In Africa, poor harvesting practices and reduced rainfall in regions like Engaruka, Tanzania, and Mauritania have worsened land fertility and agricultural productivity. Desertification leads to a loss of biodiversity, exacerbates water scarcity, and depletes aquifers. For instance, in Mauritania, these conditions have caused food insecurity, housing problems, and declines in population health. With 90% of Mauritania situated in the Sahara Desert, the nation is particularly vulnerable to the effects of prolonged drought and decreased rainfall.

The UNCCD efforts to combat desertification have focused on raising public awareness, expanding scientific knowledge, and implementing effective policies. Public concern about desertification has significantly increased, driven by initiatives like the Economics of Land Degradation (ELD), which highlight the economic costs and productivity losses due to land degradation. Major reports, including the Assessment Report on Land Degradation and Restoration and the World Atlas on Desertification, provide precise data on the severity and extent of land degradation. The Science-Policy Interface (SPI) has played a crucial role in offering scientific guidance and developing the concept of Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN), subsequently establishing it as a measurable target.

Policy advancements include LDN becoming a concrete measure, with 135 countries submitting baseline data. Tools like the LDN Assessment Tool have achieved advanced status, and governments are increasingly implementing policies to promote sustainable land management. Investments in sustainable technologies, such as the Great Green Wall of Africa, aim to restore degraded land. Initiatives like the Land Degradation Neutrality Fund align private sector interests with long-term agricultural yields, while the Drought Initiative helps countries develop stronger drought emergency plans. Additionally, policies have been negotiated to assist disenfranchised groups in accessing land, with a Gender Action Plan promoting equality in land rights and resource access.

By 2020, pledges to recover 1 billion hectares of degraded land had been made, with 128 countries planning to set targets for 2030.

Minamata Convention on Mercury

Small-scale gold mining in the Amazon has expanded significantly since the early 2000s, primarily through river dredging. This method involves mixing mercury with sediment to extract gold, which accounts for 20% of the world’s gold supply. While providing income in regions with limited job opportunities, this activity is largely unregulated and illegal. Gold mining causes deforestation, pollutes water bodies, and releases large amounts of mercury into the atmosphere, contributing over 35% of global mercury emissions.

Mercury is a naturally occurring element found in air, water, and soil. It exists in various forms: elemental or metallic mercury, inorganic mercury compounds, and organic mercury compounds. Human activities, such as gold mining, coal burning, and waste incineration, significantly increase mercury concentrations in the environment. When mercury is used in gold mining, it combines with gold to form an amalgam, which is then heated to evaporate the mercury, leaving behind pure gold. This process releases mercury vapor into the atmosphere, and the remaining mercury often contaminates soil and water.

The pollution caused by mercury has severe consequences for both human health and ecosystems. Mercury exposure can lead to neurological and developmental damage, particularly affecting fetuses, infants, and young children. In wildlife, mercury can impair reproduction, development, and behavior, with high concentrations found in various species, including songbirds. This is especially concerning for indigenous communities in the Amazon, who rely on the forest and its resources for their livelihoods.

Despite its rich biodiversity, the Amazon suffers from severe mercury pollution, with little research on its impact on terrestrial ecosystems. Jacqueline Gerson, PhD from the University of California, Berkeley in ecology, led a research team investigating mercury contamination around mining sites in Peru. The team found extremely high mercury levels in old-growth forests near gold mining areas, with concentrations 15 times higher than those in deforested or distant regions. Mercury enters forests through rain, atmospheric particles, and plant uptake, posing significant risks to ecosystems and human health.

Due to these issues, the Minamata Convention on Mercury was adopted in 2017 and it represents a critical global effort to control mercury pollution. Named after the Japanese city that suffered one of the worst cases of mercury poisoning, the Convention aims to reduce mercury use and emissions through legally binding measures. It is essential to involve local communities and organizations in creating sustainable solutions for reducing mercury release while supporting livelihoods.

GEF Funding & Financial Statements

The GEF has partnerships with over 182 countries, international institutions and the private sector. Most of GEF funding comes from pledges from donor countries, investment income from unused cash and carryover income from previous replenishment cycles. During each replenishment cycle, in-depth technical reviews of the existing projects are performed and new opportunities for funding are presented to stakeholders such as the GEF Assembly. In the financial statement, the GEF uses two units of accounts for its financial statements, namely the USD and the SDR.

Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) are the IMF’s unit of account and serve as a “reserve asset” for member countries. To illustrate, imagine you are part of an organization that creates its own coins. The head of the organization, similar to the IMF, allocates a certain number of these coins to each member. These coins are not physical currency but represent value within the organization. If this organization operates within the European Union (EU), the real currency used would be the EURO. When members need EUROS, they can exchange some of their organizational coins for EUROS to make purchases or meet financial needs. Since each member is allocated coins (analogous to SDRs), they can easily convert these coins to any other real currency among members and finance their needs, providing flexibility and liquidity within the organization.

At the IMF, members can borrow additional SDRs at low interest rates. This is feasible because the value of SDRs is based on a weighted basket of major currencies that are highly traded in the financial and economic markets. This basket includes the US dollar, Euro, Chinese yuan, Japanese yen, and British pound. The low interest rates are due to the stability and strength of these currencies, making SDRs a cost-effective option for borrowing and financial management for low-income countries.

SDRs can therefore be thought of as an international reserve asset rather than a real currency. The value of SDRs is updated daily through the London exchange market. Most of the GEF reports are calculated using SDRs, with their values often presented in US dollar equivalents.

As previously mentioned, the World Bank serves as the Trustee of the Global Environment Facility (GEF), with one of its primary responsibilities being the preparation of financial reports concerning the investment and use of GEF fund resources. The report we will be examining is based on financial data as of March 31, 2023. The GEF operates as an independent financial mechanism, providing grants and concessional funding to cover the incremental or additional costs of measures aimed at protecting the global environment and promoting environmentally sustainable development. Currently, the GEF is the largest financier of projects addressing global environmental challenges, functioning as a global partnership among 182 countries, international institutions, non-governmental organizations, and the private sector.

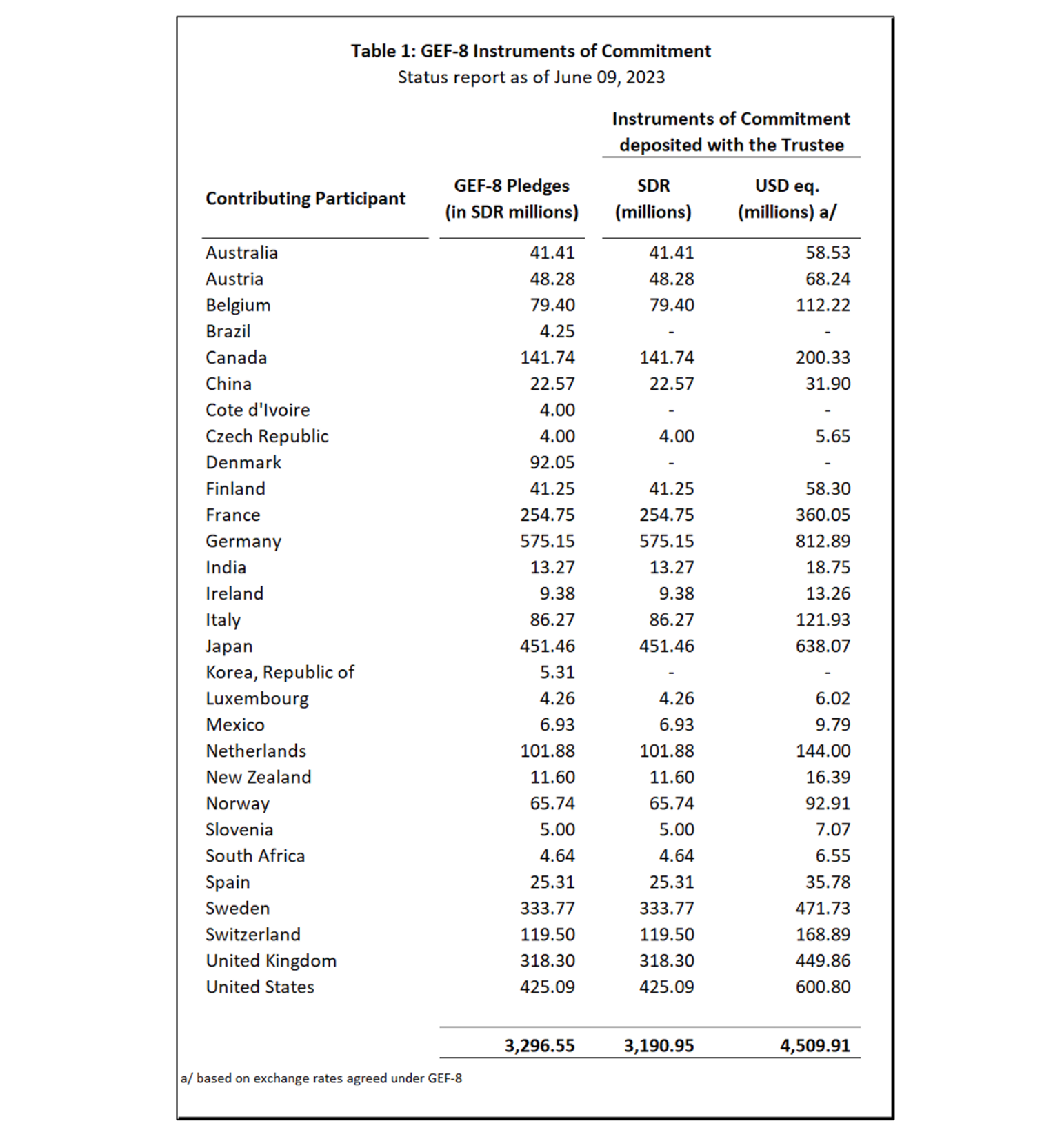

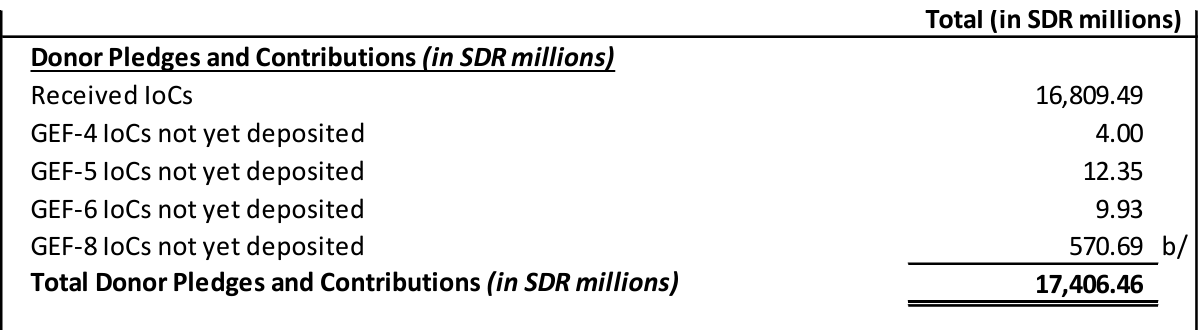

GEF receives its funding on so-called “replenishment cycles” through which member countries and partners pledge to fund GEF’s main projects. As of March 2023, there is USD 24,845 million pledged, of which 24,011 has been confirmed by deposits of Instruments of Commitments (IoC) and Qualified Instrument of Commitments (QIoC). IoC and QIoC are legally binding obligations that member countries pay to the GEF Trust Fund. With qualified IoC, full payment is not guaranteed until internal country legislation approves it but these are considered safe enough to be received in due date. Every replenishment cycle is numbered. In 2022, the eighth replenishment cycle took place, hence it is called GEF-8. Total donor pledges amounted to USD 4,659 million, of which 83% has already been deposited with the trustee as IoC or QIoC.

- Note: Unless stated otherwise, assume that March 2023 financial statements are being reviewed.

Payments related to replenishment cycles are fulfilled according to the IoC. GEF assets are not only determined by the replenishment cycles but also by investment income earned and carryover of resources. Cash is not always completely used up, and this is reinvested and carried over onto the next replenishment cycle. From there, investment income is earned. GEF receives the funds from the Trustee (The World Bank) once they are approved by the GEF Council and the CEO. These funds are meant to meet project disbursement needs and to cover administrative expenses. Funds are then allocated to the GEF Secretariat, net of cancellations and reductions.

Donor payments can take the form of cash or promissory notes. Promissory notes are legally binding promises to pay the committed amount to the Trustee. Once the promissory note is paid, the obligation is settled. Otherwise it is known as a “unencashed” promissory note, which is only settled once cash is paid. The World Bank works closely with the Contributing Participants to facilitate the deposit of Instruments of Commitment (IoCs) or Qualified Instruments of Commitment (QIoC). The full effectiveness of GEF-8 replenishment is triggered on the date the Trustee has received IoCs/QIoCs from Contributing Participants whose combined contributions aggregate to not less than 60%, or SDR 1,969.76 million, of the total contributions.

The following table shows the GEF-8 pledges. Germany, Japan, U.S., United Kingdom, Sweden and France are the member countries that provide the highest amounts of funding for the replenishment cycle.

As you can see below, around SDRs 570.7 million still need to be deposited. This is much higher than other replenishment cycles (4, 5, 6). This is expected, since cycle 8 has just occurred taken place recently in 2022.

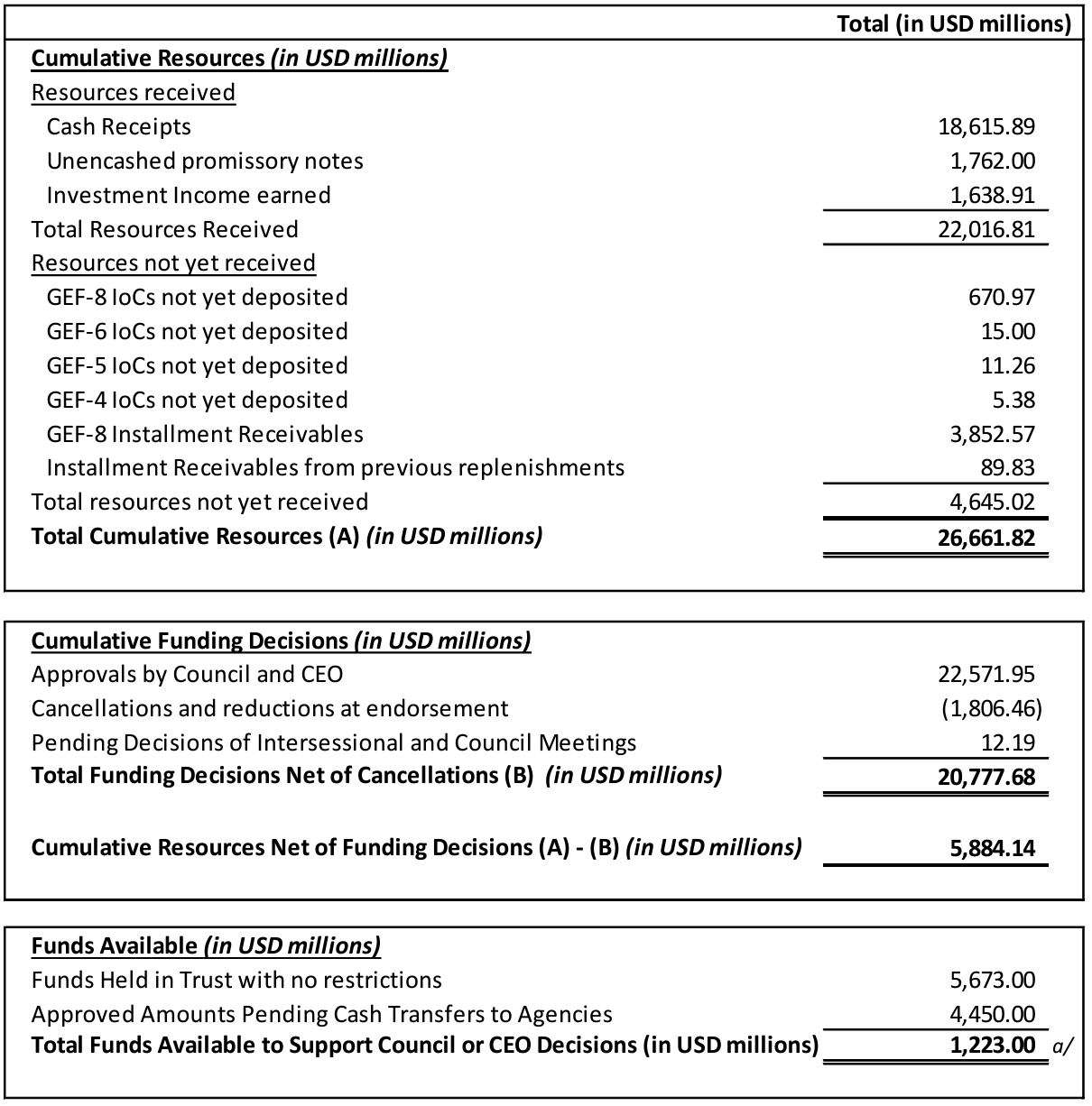

If we look at the balance sheet of the GEF, we can appreciate the cumulative resources in USD million. Resources are divided into received and not yet received. Received resources are made up of cash receipts, unencashed promissory notes and earned investment income. Cash receipts amount to USD 18.6 million, which makes up the largest asset. For non-received resources, it includes all of the IoCs that have not yet been deposited as well as installment receivables. The largest account is made up by the “GEF-8 Installment Receivables from previous replenishments”.

Once we understand the sources of cumulative resources, then we can look at where funding is going to. Circa USD 22.5 million has been approved with USD 1.8 million in cancellations with a net funding approval of USD 20.7 million. If we subtract total cumulative resources minus net funding decisions, cumulative resources final result is USD 5.8 million.

Cumulative net funding decisions represent about 78% of the cumulative GEF resources and of the cumulative resources of USD 26.6 million, around 17% represent resources not yet received. Also there might be some countries that did not deposit their IoC for previous replenishments. For example Nigeria still has around USD 5.4 million to deposit from the GEF-4 replenishment cycle. In total, from cycles 4, 5 and 6 USD 31.6 million is the total sum still pending.

Regarding the most recent GEF-8 cycle: Canada, Finland, Norway and U.S. placed QIoCs and payments have been confirmed from most of these countries already, amounting to USD 791.8 million (from USD 5.33 billion pledged).

Currently the United States is the contributing participant with the largest installment arrear payments to the GEF, which amounts to USD 88.01 million, followed by Nigeria of USD 0.90 million.

Foreign exchange risk is one of the major risks faced by the GEF. This is because most of its payments are received in other currencies. For example, if the US currency appreciates strongly against other major currencies, this could impede other countries from fulfilling their corresponding replenishment.

How does the GEF Trust Fund work?

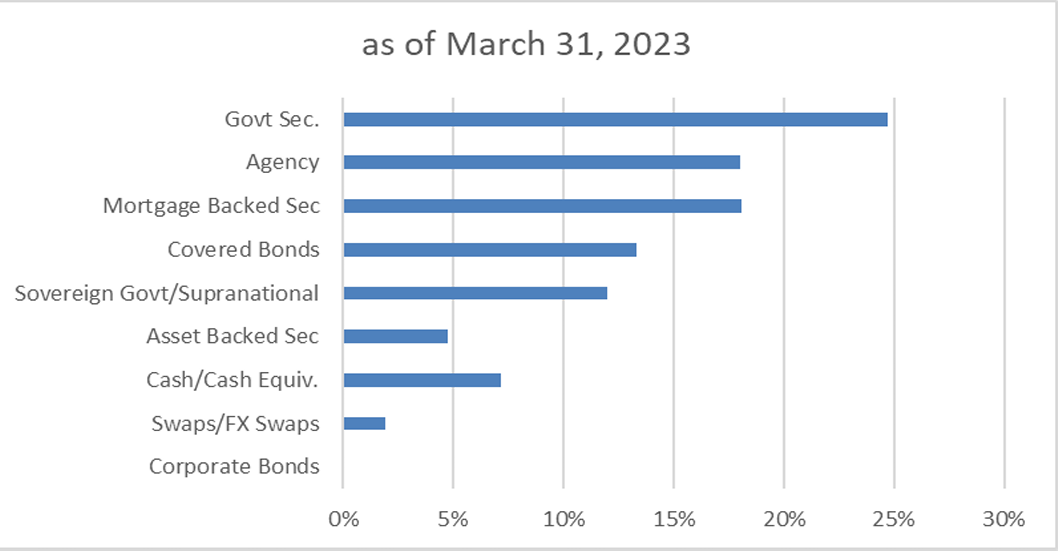

Undisbursed cash balance is invested and managed by a commingled investment portfolio for all trust funds managed by the IBRD. The GEF Trust Fund aims to optimize investment returns subject “to preserving capital and maintaining adequate liquidity to meet foreseeable cash flow needs, within a conservative risk management framework”.

As from the graph above, you can see that about 25% of the cash is investment in government securities, followed by mortgage backed securities (MBS) and agency securities.

Some terminology:

- MBS are asset-backed securities formed by pooling together mortgages. Basically the investors are “lending” money to home-owners which in place pay periodic mortgage fees (“coupon”) that pass-through eventually to the MBS investor.

- Covered bonds are debt securities issues by a bank or mortgage institution and collateralized against a pool of assets that, in case of failure of the issuer, can cover claims at any point of time.

- Swaps and FX Swaps are used to manage foreign exchange currency risks.

The GEF investment portfolio as of March 2023 is composed of high-grade fixed-income securities (sovereign, supranational, agency securities, and bank deposits). The investment portfolio is also checked against Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) ratings with AA quality (score: 7.83). Moreover, it has a low carbon risk and very low reputational risk. If you want to know how ESG ratings are calculated, please click here.

Since inception to March 2023, funding approvals made by the Council and CEO total USD 22.557 million, of which 89% was approved for projects, 7% for agency and 4% for administrative budgets. Circa 77% of the total funding goes to biodiversity, climate change and multi-focal areas. The parties responsible for the implementation of the projects have shifted over time. At the beginning of the GEF history, IBRD and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) were the major project executors. As time passed, GEF projects are now more and more executed by smaller agencies and by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP).

Two important metrics that when assessing the rate of investment at the GEF level are:

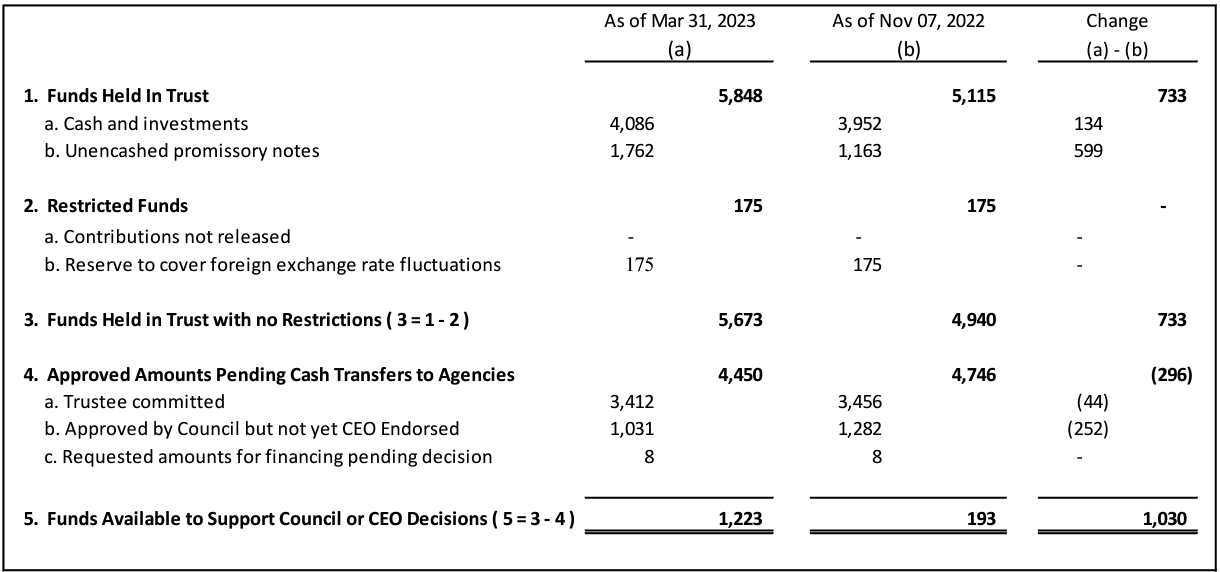

- Funds Held in Trust: It is driven by cash receipts from donors, promissory notes and investment income.

- Approved Amounts Pending Cash Transfers to Agencies: It is driven by the approval rates by the CEO/Council of the projects. Whenever projects are approved, this metric increases. When the actual amounts are transferred to agencies, there is a decrease in the metric. Essentially, approved amounts pending cash transfers to agencies reflect the committed funds that have been approved for projects but have not yet been disbursed to the implementing agencies.

As you can see, funds held in trust increased by USD 733 million, mostly driven by promissory notes while “approved amounts pending cash transfers to agencies” decreased by USD 296 million.

Bibliography

- Global Environment Facility. (n.d.). GEF-8 Replenishment. Retrieved from https://www.thegef.org/who-we-are/funding/gef-8-replenishment

- Global Environment Facility. (n.d.). How Projects Work. Retrieved from https://www.thegef.org/projects-operations/how-projects-work

- Global Environment Facility. (n.d.). Conventions. Retrieved from https://www.thegef.org/partners/conventions

- United Nations Environment Programme. (n.d.). UN Biodiversity Conference COP 15. Retrieved from https://www.unep.org/un-biodiversity-conference-cop-15

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (n.d.). What is the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/what-is-the-united-nations-framework-convention-on-climate-change

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Persistent Organic Pollutants: A Global Issue, Global Response. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/persistent-organic-pollutants-global-issue-global-response

- Stockholm Convention. (n.d.). Overview. Retrieved from https://www.pops.int/TheConvention/Overview/tabid/3351/Default.aspx

- Earth.org. (n.d.). What is Desertification? Retrieved from https://earth.org/what-is-desertification/

- Hamady, S. (2022, November 10). Desertification is Destroying Mauritania. Newsweek. Retrieved from https://www.newsweek.com/desertification-destroying-mauritania-opinion-1725160

- United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. (2022). UN DLDD Decade Highlights. Retrieved from https://www.unccd.int/sites/default/files/2022-03/UN%20DLDD%20decade%20highlights%20.pdf

- Natural History Museum. (n.d.). What is the Convention on Biological Diversity and What Does It Do? Retrieved from https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/what-is-the-convention-on-biological-diversity-and-what-does-it-do.html

- Scientific American. (n.d.). Gold Mining is Poisoning Amazon Forests with Mercury. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/gold-mining-is-poisoning-amazon-forests-with-mercury/

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Reducing Mercury Pollution from Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/reducing-mercury-pollution-artisanal-and-small-scale-gold-mining

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Mercury Emissions: The Global Context. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/mercury-emissions-global-context

- Financial Statement GEF (March, 2023). Retrieved from: https://www.thegef.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/EN_GEF.C.64.Inf_.05_GEF_Trustee_Report.pdf.