Introduction

In this article, I will discuss economic concepts and link them to real data, aiming to assess a country’s economy holistically. I have chosen Niger due to its significant potential and the challenges it shares with other Sub-Saharan countries. Additionally, I will present a waste management study conducted in Niger by leading universities and propose sustainable development solutions. Countries like Niger can be exemplary models of success if change is managed with sustainability in mind because they are not fully industrialized and can learn from developed countries’ mistakes, thereby accelerating progress. By adopting sustainable practices early on, Niger can avoid the pitfalls of rapid, unchecked development that have led to environmental degradation and social inequalities in more industrialized nations. Instead, the country has the opportunity to pave a new path that integrates economic growth with environmental stewardship and social inclusion. This approach not only ensures a balanced and resilient economy but also enhances the quality of life for its citizens, positioning Niger as a model for sustainable development in the region.

Niger’s Economic Development

Niger is a landlocked West African country and one of the poorest nations globally. There are different ways to measure poverty, but one of the most prevalent in economics is Gross Domestic Product (GDP). GDP measures the total value of goods and services produced in a country over a specific period. We can also use “Real” GDP to measure a country’s prosperity. Real GDP adjusts for inflation using a base year (e.g., 2021). For example, if a kilogram of apples was worth $2 in 2021, real GDP calculations would use this price to measure growth in subsequent years. This adjustment allows economists to determine whether an economy has grown or contracted in terms of actual output, excluding inflation’s effects. In traditional economics, more output is desirable as it can enhance living standards, either through domestic consumption or exports.

Niger is one of the ten largest African countries by land mass, ranking as the 6th largest and covering over 1,267,000 square kilometers. Situated in a dry, hot region, Niger is part of the Niger Basin and is considered a low-income country with challenges such as chronic poverty, low investment, subsistence agriculture, and dependence on rainfall for water, crops, and livestock. The nation experiences chronic political instability, with frequent coups, and in 2023, it exited the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to form the “Alliance of Sahel States” (AES) with Burkina Faso and Mali. ECOWAS was founded in 1975 to promote economic cooperation among member states to improve living standards and economic development. However, after military coups, the three nations criticized ECOWAS for failing to address jihadist violence and for being influenced by foreign powers, betraying its founding principles.

On July 26, 2023, Niger underwent its latest military coup when the Presidential Guard ousted President Mohamed Bazoum, citing issues of poor governance and security. This upheaval resulted in Niger losing international assistance—amounting to approximately 8% of its GDP—and facing international isolation by ECOWAS and the African Union. The coup also triggered border closures, leading to food shortages, inflationary pressures, social tension, and escalating jihadist violence in the southern regions of the country.

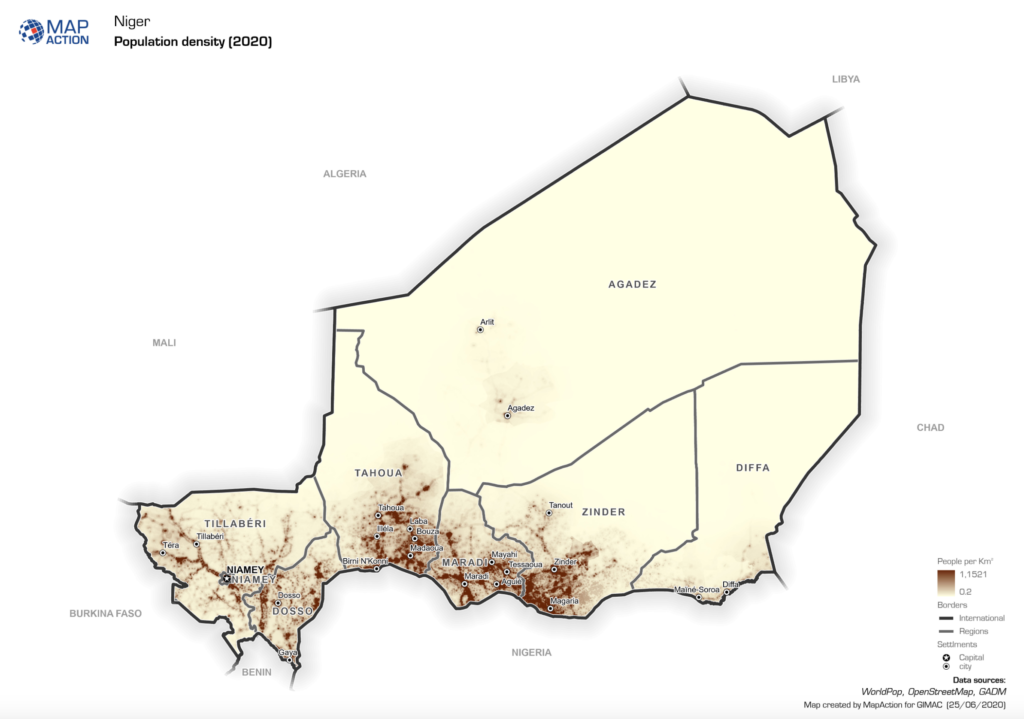

Niger’s GDP stands at USD 18.82 billion, in comparison to Mali’s USD 21.66 billion, Senegal’s USD 35 billion, and Spain’s USD 1,650 billion. This indicates that Niger produces fewer goods and services than Mali, Senegal, and significantly less than Spain. GDP is often influenced by a country’s size and population density, which describes the number of people living per square kilometer. Generally, smaller countries produce less than larger ones, and densely populated countries produce more than sparsely populated ones.

Niger’s population distribution is greatly influenced by its geography and climate, with approximately 75% of its territory covered by the Sahara desert. Consequently, 96% of the population resides in the southern part of the country, which spans about 300,000 square kilometers. While the national population density is approximately 16 inhabitants per square kilometer, the capital city, Niamey, has a density of about 6,000 inhabitants per square kilometer. The southern region, supported by the Niger River and higher rainfall, sustains agriculture and hosts the majority of the population, both nomadic and settled. The northern and central regions, characterized by mountain masses and high plateaus, are sparsely inhabited and primarily used by nomadic pastoralists for cattle raising.

Niger has the highest fertility rate in the world, with an average of 7 children per woman, resulting in the highest natural population growth rate globally at 3.9% per year between 2010 and 2015. The level of urbanization in Niger is the lowest in Africa, with only 17% of the population residing in urban areas with more than 10,000 inhabitants. The capital, Niamey, currently has a population of about 2 million, which is projected to grow to 6.5 million by 2050. The average household size in Niger is approximately 6 people, with the national average being around 7.7 people per household. These demographic figures are crucial for understanding waste management practices and other forms of investment and infrastructure necessary for improving living standards.

Unlike many regions worldwide where villages and rural areas suffer from depopulation and emigration to large urban centers, Niger is experiencing the rise of numerous new small towns. The number of towns with fewer than 30,000 inhabitants has increased from 17 in 1990 to 51 in 2015. This trend has created a unique network of villages that do not excessively strain major urban resources but rather demand the availability of services in semi-rural areas. Notably, the average distance between towns has decreased from 78 km to 38 km, underscoring this point. Thus, we observe densely packed settlement patterns, predominantly situated near the Niger River, emphasizing the critical role of water resources in the Sahel.

Policymakers should prioritize extending basic service coverage across a broader network of towns and villages, rather than concentrating them in major cities. This approach would enhance the quality of life in rural and semi-rural areas and foster a diverse economy with local hubs that could evolve into platforms for knowledge exchange and services. Currently, infrastructure remains insufficient to support this growth.

To measure poverty, various standards are typically employed. The World Bank utilizes the international poverty line, currently set at USD 2.15 based on 2017 prices. This means anyone living on less than $2.15 a day is considered to be in extreme poverty. In 2019, approximately 648 million people worldwide fell into this category.

International poverty lines are periodically updated to account for changes in prices. Factors such as inflation, energy, and food price fluctuations lead to upward revisions. For instance, in 2011, the international poverty line was set at USD 1.90.

The World Bank employs different poverty lines for different income levels. The international poverty line (IPL) is primarily used to measure extreme poverty and is most relevant for low-income countries. For wealthier nations, two higher thresholds are more pertinent: $3.65 for lower-middle-income countries and $6.85 for upper-middle-income countries, based on 2017 purchasing power parities (PPPs).

Purchasing power parities (PPPs) are the rates of currency conversion that try to equalize the purchasing power of different currencies, by eliminating the differences in price levels between countries. The basket of goods and services priced is a sample of all those that are part of final expenditures: final consumption of households and government, fixed capital formation, and net exports. This indicator is measured in terms of national currency per US dollar.

Additionally, the World Bank has developed the societal poverty line (SPL), which factors in the average well-being of people in a specific country. According to 2011 data, the SPL is defined as $1.00 plus half of a country’s median spending on goods and services. If this amount is less than the international poverty line, the latter is used instead. As countries become wealthier, the SPL increases. With updated 2017 data, the SPL is adjusted to $1.15 plus half of the median spending, adhering to the same rule where the higher value applies.

If we take into account the different poverty lines:

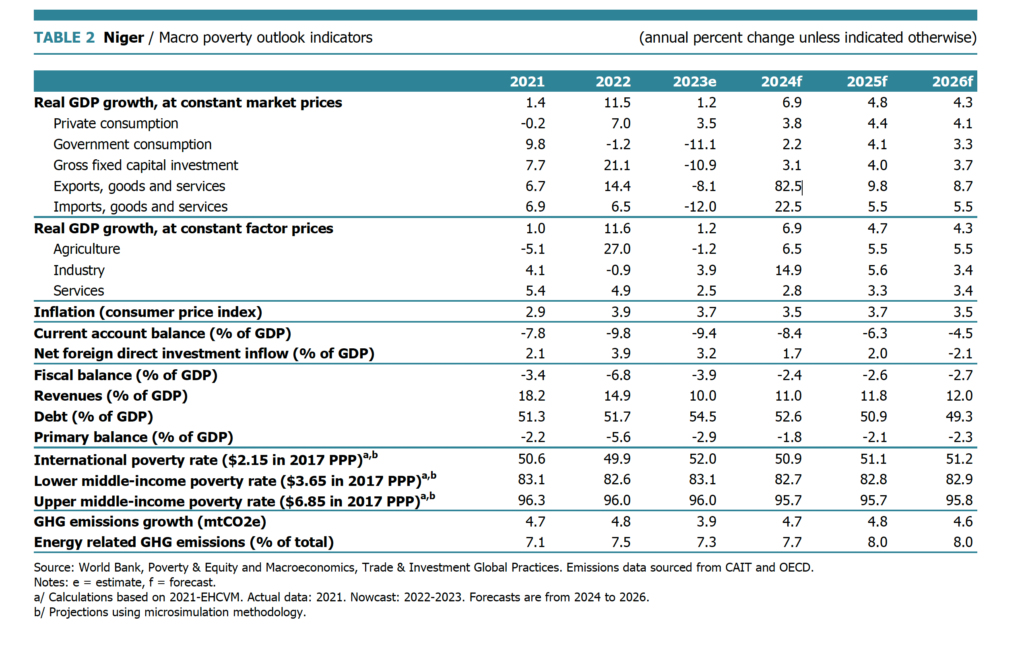

- At the international poverty line of $2.15, around 50% of Niger’s population is currently below this threshold, with projections indicating an increase to 51.2%. This is primarily because the population is growing faster than the rate of poverty reduction.

- For the lower middle-income poverty line of $3.65, 83% of the population is expected to remain below this level over the next three years.

- At the upper middle-income poverty line of $6.85, 96% of the population is anticipated to stay below this threshold for the coming three years.

There are various ways to measure GDP, and we will focus on the output and expenditure approaches. The output approach calculates the total value of all goods and services produced within a country, accounting for total production outputs minus inputs such as raw materials and intermediate goods. This method captures economic activity across sectors like manufacturing, services, and agriculture.

Conversely, the expenditure approach assesses the total spending on all finished goods and services produced within a country during a specific period. This includes private consumption, capital investment, government spending, and net exports.

Let’s delve into the components of the expenditure approach:

- Private Consumption: This encompasses the market value of all goods and services purchased by households, excluding dwellings but including imputed rent for owner-occupied homes and government payments and fees.

- Government Expenditure: This includes all current government expenditures for goods and services, employee compensation, and most national defense and security expenditures, excluding military spending for capital formation.

- Gross Fixed Capital Investment: This covers land improvements, purchases of plant, machinery, and equipment, and construction of infrastructure such as roads, railways, schools, offices, hospitals, and residential and commercial buildings.

- Exports: These represent the value of all goods and services supplied to the rest of the world, including merchandise, transport, travel, royalties, and various services, excluding employee compensation and investment income.

- Imports: These represent the value of all goods and services acquired from the rest of the world, using criteria parallel to exports but in reverse. Imports reduce GDP since they constitute an expenditure outflow.

Over 75% of Niger’s workforce is involved in subsistence agriculture, making them particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change. While the country’s GDP growth has primarily been driven by mining exports and agricultural output, this reliance has resulted in an undiversified economy susceptible to climate fluctuations, commodity price volatility, and external demand shocks. Between 2011 and 2020, Niger’s GDP growth fluctuated significantly, ranging from 2.4% to 10.5%. In 2022, the nation saw robust GDP growth at 11.5%, but this was followed by a sharp decline to a mere 1.2% in 2023, largely due to political instability, including ECOWAS’s exit, sanctions, and a seven-month restriction on the flow of goods and services with its African partners.

Looking ahead, GDP growth is forecasted to reach 6.9% in 2024, 4.8% in 2025, and 4.3% in 2026. This anticipated recovery is mainly attributed to the lifting of sanctions and the commencement of large-scale oil exports. However, Niger is expected to face challenges such as reduced regional trade due to ECOWAS’s departure, elevated international financing risks stemming from political instability, terrorism threats, and ongoing underinvestment in sanitation and water supply infrastructure. Budget deficit due to low government revenues continues to be another obstacle for capital investment. In the following sections, we will analyze Niger’s economy from both the expenditure perspective and the output approach.

Economic Analysis using the Expenditure Approach

Exports & Imports in Niger

Niger has suffered from a chronic account deficit for many years (current account is exports minus imports of goods and services). As of 2022, exports constitute USD 1.48 billion, making up approximately 8.91% of the total GDP of USD 16.61 billion. Imports are USD 3.78 billion (circa 22% of the 2022 GDP levels), constituting a significant portion of Niger’s economy. This disparity between exports and imports has contributed to the persistent account deficit, placing additional stress on the country’s fiscal health and economic stability.

In 2022, Niger leading exports included uranium and thorium ores, which comprised 31% of exports, followed by petroleum oils and waste oils at 28%, and gold at 16.6%. Other notable exports were various vegetables, palm oil, bulldozers, locust beans, live bovine animals, motor vehicles for goods transport, and worn clothing. The top four export partners were France, accounting for 33% (140 million US$) of exports, Mali with 18.7% (79 million US$), Nigeria at 16% (67 million US$), and the United Arab Emirates with 8.9% (37 million US$). The remaining export partners collectively represented 23.4% (99.67 million US$) of Niger’s exports.

Niger relies heavily on various imports to meet its domestic needs, with the top 10 imports in 2022 comprising a diverse range of goods, including rice (14.4%, $546 million), parts and accessories of articles (8.99%, $339 million), aircraft parts (6.38%, $241 million), other aircraft and spacecraft (3.71%, $140 million), other tubes and pipes (3.38%, $127 million), petroleum oils and waste oils (2.25%, $85 million), Portland cement, aluminous cement, slag cement, and hydraulic cement (2.12%, $80 million), palm oil and its fractions (1.86%, $70 million), electrical energy (1.85%, $70 million), and medicaments (1.83%, $69 million). Niger’s top import partners in 2022 include China (23%, $904 million), France (21%, $794 million), India (10.2%, $387 million), Nigeria (7.66%, $289 million), Germany (5.08%, $192 million), Thailand (3.74%, $141 million), the USA (3.19%, $120 million), Pakistan (2.5%, $94 million), the United Arab Emirates (2.48%, $93 million), and Japan (1.77%, $67 million).

Exports increased at 14.4% in 2022 and are forecasted to decrease by 2023 by 8.1% due to commercial and financial sanctions and border closures lasting around 7 months and a pause of development assistance. This is driven by the political crisis and coup d’etat experienced in July 2023. By 2024, exports are expected to fully recover and continue growing at around 8-10% per annum (2025-2026 forecast). On the other hand, imports are expected to decrease by 12% in 2023, increase to normal levels by 2024 and increase at a rate of 5.5% per annum between 2025 and 2026.

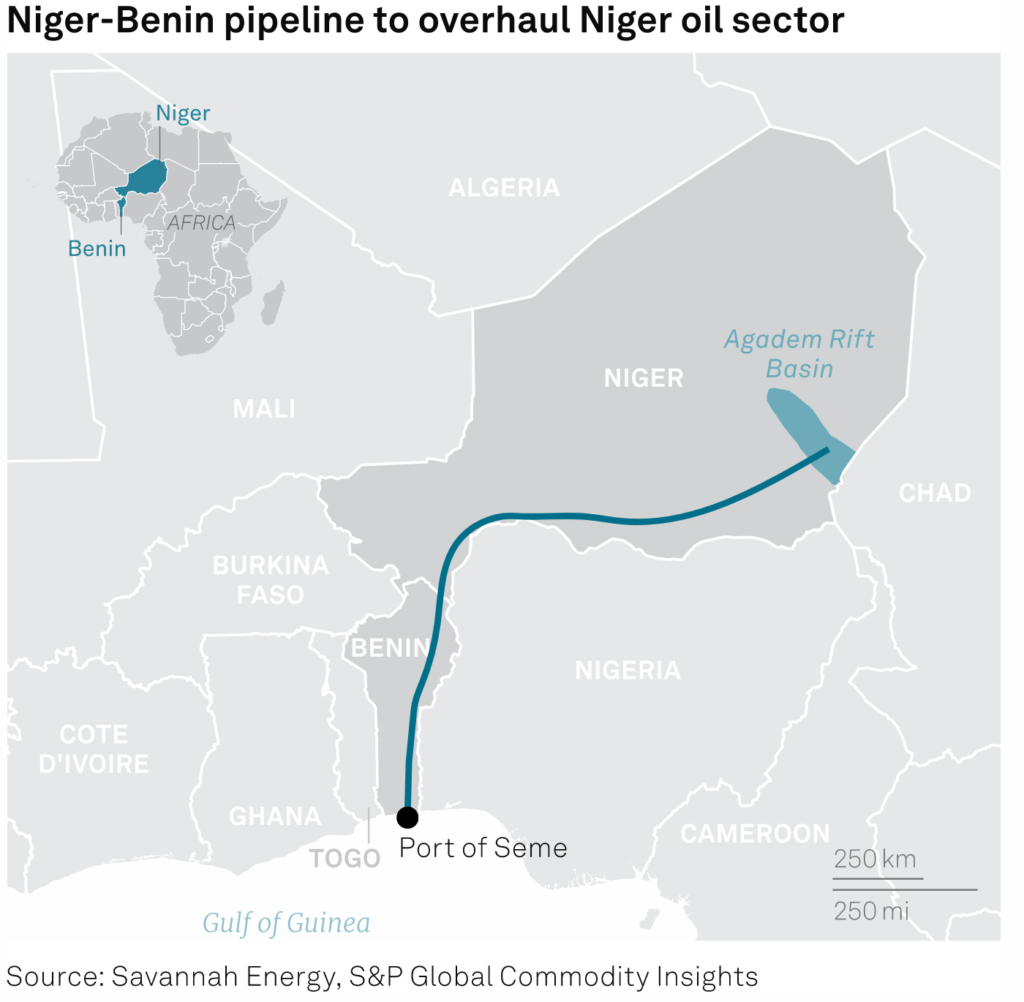

A new oil pipeline, operational since late 2023, is expected to achieve peak production of 110,000 barrels per day (bpd) during the 2024-2025 period. Production will gradually decline until the pipeline reaches the end of its economic life in 2051. China National Petroleum Corp holds a 57% stake in the oil well, while Taiwan CPC owns 18%, and the Niger government controls the remaining 25%. This underscores the vital role of foreign investment in extracting and selling the country’s resources. The oil must be transported via pipeline and loaded at Benin’s port, emphasizing the importance of regional cooperation given Niger’s landlocked geography.

We could argue that Niger’s strengths are its uranium, gold and oil reserves that can serve as catalysts for income generation and growth. However, this can also be a weakness since Niger is exposed to commodity-price fluctuations. Since the formation of the AES, its relationship with France has strained and it may pose a risk if it does not find other suitable and reliable trade partners in the future.

Did you know?

Niger gained independence from France in 1960 and has been exporting uranium since 1957. France is one of Niger’s primary uranium importers, using it for nuclear power production. By the end of 2019, Niger’s cumulative uranium production reached approximately 150,000 tU, with a production of 2,248 tU in 2021 alone. Since February 2012, uranium sales have been conducted with partners based on a government-determined extraction price of $145 USD/kgU. Niger holds 5% of the world’s proven uranium reserves. It’s important to note that uranium is not traded on open markets; instead, contracts are privately negotiated between buyers and sellers, creating a lack of transparency. However, industry prices can be inferred from sources like month-end prices published by UxC and TradeTech.

Most uranium contracts worldwide (80-90%) are established as long-term supply agreements, which involve deliveries on specific dates at predetermined prices. The remaining contracts (approximately 10%) occur as “spot market” transactions. Although there is no true spot market, this term signifies irregular and short-term purchases, typically conducted through traders or brokers. Long-term contracts are generally favored by nuclear power plant operators to mitigate price volatility and ensure a consistent supply. While this approach limits profit potential when uranium prices drop, it is preferable to avoid exposure to rising prices that could disrupt plant operations. Shutting down a nuclear plant is costly and complex.

Currently, the primary driver of uranium production is the demand for low-carbon electricity. Nuclear power accounts for about 10% of the world’s electricity and is the second-largest source of low-carbon power globally, contributing 26% of the total in 2020. Uranium prices have remained sluggish since 2008, but in 2023 they have begun to gain momentum. This shift suggests that nuclear power plants will likely bear most of the costs. However, it is promising news for uranium exporters like Niger, as they stand to benefit from higher export tax revenues.

Infrastructure & Fixed Capital Investment in Niger

Niger requires increased fixed capital investment to ensure its continued growth. Chronic underinvestment in key sectors such as energy, infrastructure, mining, and water sanitation has hindered the country’s development. Factors like political instability, terrorist threats, a low-skilled workforce, and inadequate infrastructure have historically impeded substantial foreign direct investment (FDI).

In response, the Nigerien government established the High Council for Investment in 2017 to attract more international capital. Additionally, the government has launched the Guichet Unique du Commerce Exterieur, an electronic platform designed to streamline import-export processes for both domestic and international entrepreneurs and firms. This platform provides clear guidelines and procedures for the importation and exportation of goods in Niger.

A noteworthy investment by the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) culminated in 2023 with the completion of a significant oil pipeline linking the oil-rich Agadem Rift Basin in the Koulele region to Benin’s port of Seme. Previously, landlocked Niger produced approximately 20,000 barrels per day for domestic consumption. The new pipeline is expected to increase production to 110,000 barrels per day, contributing up to 13% of Niger’s GDP by 2025. This development will enhance government revenues, enabling greater debt servicing and infrastructure investments. Exports are projected to rise by 89% compared to 2023 levels, and the increased oil revenues will further accelerate Niger’s economic growth.

Investment in Niger has historically focused on raw materials and commodities, such as uranium (approximately 500,000 metric tons in reserves), gold, coal (75 million tons in reserves), limestone, iron, salt, phosphate, as well as industrial and construction materials. Uranium reserves are notably significant, comprising around 5% of global reserves, with extraction predominantly managed by French companies. Chinese and Turkish firms have concentrated their efforts on the oil and construction sectors, while Indian companies have maintained a presence in the telecommunications sector for over two decades. Moroccan and Lebanese entrepreneurs traditionally operate in the retail sector, owning businesses related to clothing, food, and dry goods.

Key investment opportunities in Niger lie in agriculture, transportation, further development of road infrastructure, and the construction sectors. Although U.S. investment remains minimal, there is growing potential interest in the energy and cybersecurity sectors. However, limited internet connectivity, inadequate road and energy services, the presence of violent extremist organizations, and political instability have deterred U.S. firms from investing in Niger.

Niger faces significant challenges with electrification, as only 15% of the population has reliable access to modern electricity, impeding economic growth and development. To address this, several initiatives are underway. The Nigerien Agency for the Promotion of Rural Electrification (ANPER) aims to achieve universal rural electrification by 2035, with a focus on solar mini-grids to deliver cost-effective and rapid energy access to rural areas. A mini-grid is a small-scale electricity system that generates and distributes power locally, operating independently from the national grid. Ranging from a few kilowatts to 10 megawatts, mini-grids can serve households, businesses, agricultural, productive, and semi-industrial loads. They can be run by various entities, including state utilities, private companies, and communities, and can use diesel, renewable sources, or a combination of both. Green mini-grids primarily use renewable energy.

In January 2019, ANPER, supported by USAID and Power Africa, launched a nationwide feasibility study on mini-grid development to attract international developers and private sector investment. The study proposed an innovative approach: aligning existing telecommunication towers with solar mini-grids, independent of the national electricity grid, to reduce rural electrification costs by leveraging existing user densities and telecom research.

Power Africa provided ANPER with tender documents and identified necessary policy reforms, including mini-grid licensing procedures and grid encroachment regulations, to attract private investment. These documents address the regulation of decentralized energy systems, emphasizing the rights and responsibilities of the national grid and mini-grids. Key considerations include:

- Service levels: Ensuring reliable electricity access with minimal disruptions for users.

- Tariff structures and compensation mechanisms: Clearly assigning revenues and costs to either the mini-grid or national grid system, and providing warranties and backup services in case of disruptions.

- Technical standards: Incorporating standards throughout the process, including potential future integration between mini-grids and the national grid.

- Fairness and investment protection: Safeguarding consumers from discriminatory practices by electric companies and protecting private investment from hostile takeovers and expropriation.

One advantage of Niger’s current underinvestment is the opportunity to learn from developed nations’ mistakes and fast-track investment in green technologies, achieving carbon-neutral energy in years rather than decades. The lack of sunk costs and the absence of existing infrastructure modifications allow Niger to invest in the latest energy-efficient and renewable technologies. Niger’s solar mini-grid initiative could be enhanced by partnering with technology companies like Odyssey Energy Solutions, which implement remote monitoring and control technology for mini-grid developers. This involves providing real-time operational data and technical training, enabling developers to accurately understand demand and supply, and efficiently manage peak hours.

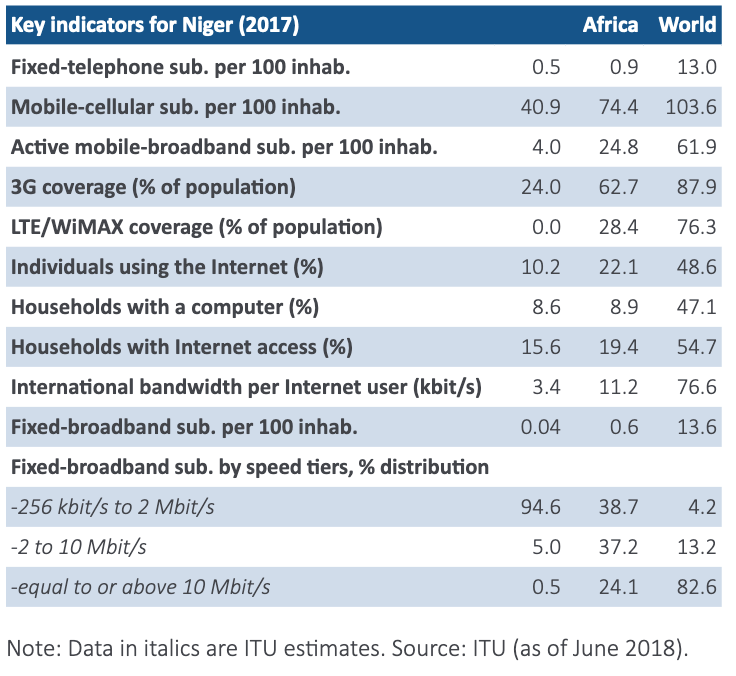

In 2001, Niger implemented reforms in the ICT sector to foster competition, effectively liberalizing the market and issuing licenses to multiple operators to provide ICT coverage to the Nigerien population. Between 2012 and 2017, approximately USD 548 million was invested, predominantly by mobile operator companies. By 2023, Niger had around 6 million internet users, representing an internet penetration rate of 22.4%. Social media users totaled 467.9 thousand, accounting for only 1.8% of the population. Additionally, there were about 14.59 million active mobile cellular connections, equating to 54.7% of the total population.

This low penetration is understandable given that over 50% of the population is below 15 years old. Consequently, underpenetration is likely to persist due to high population growth rates and the youthful demographic structure. Furthermore, approximately 83% of the population resides in rural areas, contributing to low internet usage levels. Nevertheless, internet users increased by 3.2% compared to 2022, and this growth is expected to accelerate in the coming years due to advancements in ICT and telecom networks.

In the mobile market, Airtel is the leading operator, owned by the Indian mobile group Bharti. It was launched in 2001 under the CELTEL brand. Other operators include Orange, which is 93% owned by Orange France, Niger Telecom, the national operator created in 2016 from the merger of SONITEL and SAHELCOM, and MOOV, which is 90% owned by Etisalat. Airtel holds the largest market share, followed by MOOV. While overall mobile penetration in the country is low, urban mobile penetration is high, with approximately 87.9% penetration among individuals over 15 years old. This suggests that as the population ages (though not expected soon), mobile penetration for the entire population is anticipated to rise significantly. 4G services have been available under Airtel Niger since July 2019 and currently cover Niamey, with plans to expand to other major cities soon. The 3G network was launched in 2011 by Orange, but Airtel dominates the 3G subscriber market, holding over 76% of subscriptions. Most of the ICT investment have taken place by CELTEL followed by MOOV and Niger.

On the fixed line services, Niger Telecom leads the fixed-telephone market with most subscriptions via wireless CDMA. Niger Telecom assets include 3 812 km of fiber-optic cable which connect Benin, Burkina Faso, Nigeria and further investment was financed by the African Development Bank in 2017 with additional 1 007 km of optical fiber connecting Niger to Algeria, Chad and Nigeria.

Note: CDMA stands for Code-Division Multiple Access which was used in 2G and 3G wireless communication and allows multiple signals to share a single transmission channel, thereby optimizing bandwidth usage. What this essentially means is that CDMA assigns a unique “code” to each user allowing people to communicate efficiently and makes it differentiable from other users. This is in contrast to GSM technology, which essentially combines TDMA and FDMA technologies in one. What this means is that GSM splits the communication into different “areas” and assigns each user to a specific time slot or frequency.

- FDMA (Frequency Division Multiple Access): Allocates different frequency bands to different users.

- TDMA (Time Division Multiple Access): Allocates different time slots to different users within the same frequency band.

- CDMA (Code Division Multiple Access): Allows multiple users to share the same frequency band by assigning a unique code to each user, enabling simultaneous communication without interference.

According to research, telecom service revenue in Niger stands at approximately USD 380.5 million and is projected to grow at a CAGR of over 7% from 2023 to 2028, driven by sustained revenues from mobile data and fixed broadband services. This translates to around USD 14 per capita revenue, compared to Senegal’s USD 1.4 billion or USD 77 per capita (including TV services). The African Infrastructure Country Diagnostic Report (2011) underscores the importance of an efficient telecom market for expanding the customer base and offering affordable prices. This efficiency helps bridge the coverage gap, reduces costs for telecom companies, and enables them to serve more customers.

Ongoing projects to enhance connectivity in Niger include the “Smart Village Project for Rural Growth and Digital Inclusion (PVI),” which aims to connect 2 111 villages to mobile and broadband services over the next six years. This initiative includes digital infrastructure, financial education, and the creation of agricultural and farmer digital platforms to reduce information asymmetries in prices and volumes and enhance financial inclusion in the region. The investment amounts to USD 107 million and is expected to benefit 1.4 million people. The project is managed by the National Agency for the Information Society of Niger and primarily funded by the World Bank with a grant of USD 100 million, aiming to provide internet connections to over 85% of the population.

Road infrastructure is a critical economic and social asset for countries, as it facilitates investment opportunities in sectors such as real estate, construction and development of previously underutilized areas. It also enhances living standards by establishing physical connections between regions that were once difficult to traverse, thereby improving the transportation of goods and people. Niger’s road network is approximately 18 950 km of roads, with 21% being primary paved roads, predominantly located in the Niamey-Nguime corridor in the south of the country, where the majority of the population and economic activities are concentrated. Secondary roads, which account for around 13.5% of the total network, are generally gravel. The remaining network comprises of dirt roads, tracks, trails and other rural pathways.

Research indicates that approximately 40% of paved roads are in good condition, while the remainder are in poor condition, in urgent need of maintenance and repair. Sustainable financing and the creation of stable revenue streams for road expansion, development, maintenance and repair remain significant challenges. This is partly due to the low traffic density on many roads and the inability of low-income users to afford tolls to cover these costs. Currently, economic resources are allocated by CAFER–the government entity responsible for road maintenance–and are partly funded by the Ministry of Equipment and road tolls. Most of the rehabilitation and maintenance funds are sourced from grants and loans provided by international entities such as the World Bank, the European Union, Development Banks and the Chinese government.

According to the African Infrastructure Country Diagnostic Report (2011), Niger’s road network density is notably low at 13 km per 1,000 km², compared to the average of 132 km per 1,000 km² in other low-income countries. Additionally, GIS-based rural accessibility, defined as the percentage of the rural population living within 2 kilometers of an all-season road, stands at merely 15%, lagging behind the 25% observed in similar economies.

Most of Niger’s paved roads are described as “overengineered,” necessitating higher maintenance than warranted by the actual average annual daily traffic (AADT), which is approximately 387 vehicles per day. This figure is significantly lower than the AADT of 1,131 vehicles per day in other low-income countries and 2,451 vehicles per day in middle-income countries. Notably, around 53% of Niger’s paved roads experience less than 300 AADT, raising questions about the justification for such investments.

Concerning road safety, the general lack of road maintenance poses significant risks, particularly when driving at night or on unpaved roads where potholes and bumps are prevalent. Reckless driving is widespread, particularly in minibuses where safety standards are often neglected, leading to overloading of passengers and freight beyond authorized limits. Four-wheeled vehicles are highly sought after, and incidents of banditry and theft are common, especially in the northern regions and along the borders with Mali and Nigeria. Violent assaults and robberies, often linked to extremist groups, can occur in these areas.

The Logistics Performance Index (LPI) is a benchmarking tool designed to help countries identify and address challenges in trade logistics. Based on surveys from global freight forwarders and express carriers, it combines qualitative and quantitative data to assess the logistics “friendliness” of countries. It measures performance on both international and domestic logistics supply chains, offering scores from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better performance.

The African Infrastructure Country Diagnostic Report (2011) evaluated the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) for Niger, revealing that it was higher than the average for Sub-Saharan African countries but lower than other West African nations such as Senegal, Benin, Togo, Guinea, and Nigeria—all of which have access to ports. The study identified significant inefficiencies in Niger, including challenges in transporting goods both within and beyond the country, largely due to the poor quality of infrastructure prevalent in neighboring countries. For instance, the import process in Niger took an average of 64 days compared to 39 days for the region. Transport costs accounted for 40% of the total import-export expenses, whereas the average in Low-Income Countries (LICs) was 32%, and only 18% for Middle-Income Countries (MICs). Export costs alone in Niger were 70% higher than the average for other Sub-Saharan countries.

Several factors contribute to these issues. Firstly, as a landlocked country, Niger faces ongoing trade balance deficits, importing more goods than it exports. The nearest operational ports, the Port of Cotonou in Benin and the Port of Lomé in Togo, are experiencing severe challenges. For example, the Port of Cotonou operates at 200% capacity, resulting in additional costs of approximately $180 per container. The pre-berth waiting time (the time it takes on average to dock) for vessels is around 48 hours—the highest in West Africa—while truck cycle times average 6 hours, compared to a global best practice of 1 hour. Similarly, logistic performance indicators at the Lomé port reflect inefficiencies; the container dwell time is up to 13 days versus international standards of 7 days or less. Administrative costs and bureaucratic red tape account for a significant portion of overall import costs, reaching up to 23% in the Cotonou-Niamey corridor and 35% in the Lomé-Niamey corridor.

It is noteworthy that Lomé port is one of the busiest in West Africa, handling over 1.5 million TEUs per year as of the report, compared to approximately 460,000 TEUs in 2011. The port can now accommodate Post-Panamax vessels and serves as a trans-shipment hub, where containers are transferred to smaller ships for distribution to other regional ports. Investments in capacity, governance, and management are essential to reduce the costs associated with the import and export processes for Niger. In 2011, 70% of the time spent was due to port red tape and freight handling, creating significant bottlenecks.

Many African countries uphold bilateral agreements for cargo transit, typically allocating two-thirds of the cargo to landlocked country carriers and one-third to transit country carriers. Countries such as Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso, which lack sea access, rely heavily on these agreements. An outdated European transport quota system known as the “tour de rôle” is still in use. This system operates on a “first come, first served” or FIFO basis for cargo allocation, controlled by freight organizations and associations. Consequently, truck operators may wait at ports or loading areas for weeks before their turn for loading arrives.

The European Union banned this quota system in 1996 due to its adverse effects on transport costs and efficiency. Commissions paid to associations inflate transport costs, while truck utilization declines, leading to long queues at seaports. Additionally, the system diminishes incentives for transport quality and healthy competition, as freight allocation is unrelated to the service quality and price of truck operators. This environment also fosters corruption, with bribes becoming a common practice for bypassing waiting lanes, among other issues. Lastly, the “tour de rôle” system can be argued to contribute to truck overloading practices that damage Niger’s roads, leading to more frequent maintenance and repairs. For instance, there have been reported cases of trucks being loaded with over 70 tonnes, despite the maximum allowable weight for six axles being only 51 tonnes.

Food Security & Agriculture in Niger

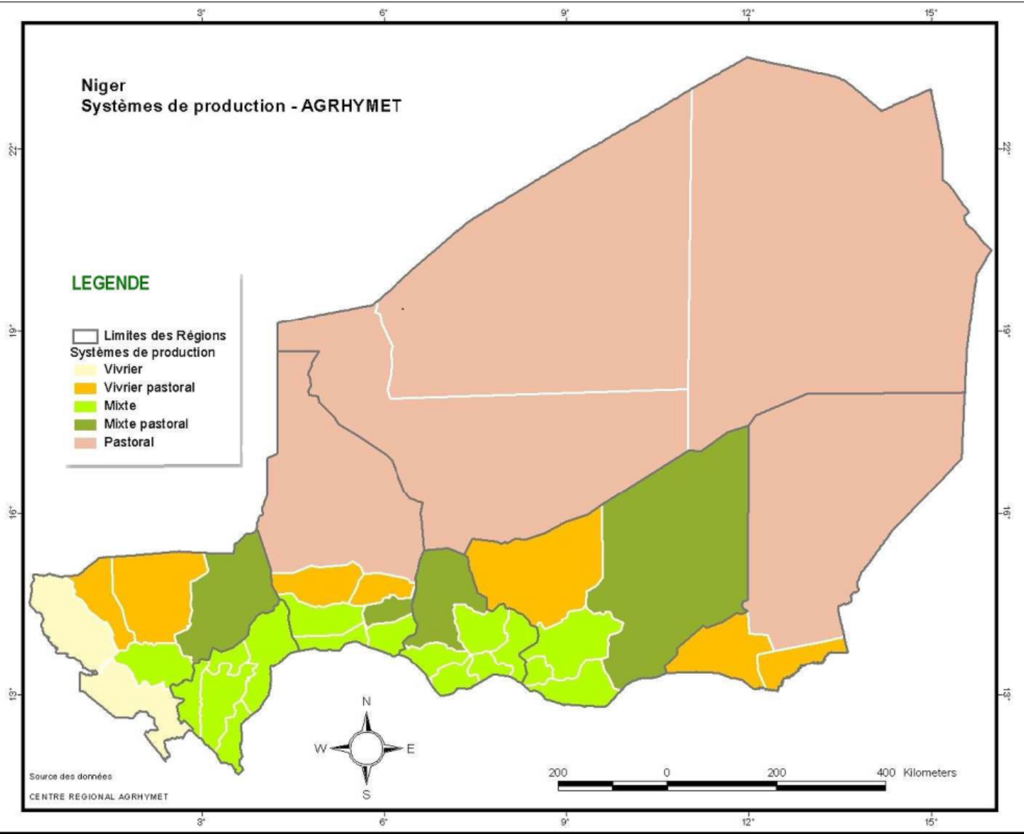

Niger’s economy is predominantly agricultural, with agriculture constituting approximately 40% of its annual GDP. Spanning over 1.26 million square kilometers, Niger is largely covered by desert, with a predominantly hot and dry climate. The country is divided into distinct agro-ecological zones based on annual rainfall, which influences the economic activities in each region.

In the Northern Region, which is mainly desert, there is minimal agricultural or livestock activity due to its low annual rainfall of 0 to 50 mm. Moving southward, the sub-Saharan pastoral zone receives about 50-200 mm of rainfall annually, while the Sahelian agro-pastoral zone receives 200-500 mm. The most southern region, the Sudano-Sahelian zone, borders the Niger River and receives 600-800 mm of annual rainfall, making it the primary area for agricultural activities. Irrigated areas, predominantly rain-fed, constitute only 10% of the territory and are sustained by permanent and semi-permanent water sources.

Agriculture in Niger is largely subsistence farming, with smallholders cultivating around 125,000 square kilometers (12.5 million hectares), expanding at a rate of 2% per annum due to population growth and increased food demand. The major crops include pearl millet (46% of total cultivation), sorghum (18%), and cowpea (32%). Other crops such as cassava, sweet potato, rice, maize, wheat, fonio, cotton, and groundnuts are also cultivated. Typically, crops are grown once a year during the rainy season, with some exceptions in irrigated areas that allow for a second crop during the dry season.

Soil types in Niger are heterogeneous, requiring crops to be planted according to the specific area where they grow best. Intercropping, the practice of growing two or more crops in close proximity, is common and offers several advantages, including efficient use of light, water, and nutrients, potentially leading to improved yields and income. It also reduces pest densities and enhances cover crop management, which helps prevent soil erosion.

Despite these practices, Niger’s agriculture faces significant challenges that contribute to food security issues. The country is highly vulnerable to changes in rainfall and droughts, which lead to low crop yields and decreased soil fertility. Additionally, farmers struggle to access quality inputs such as seeds and fertilizers, a situation worsened by the high inflation experienced in 2023 due to global trends and regional sanctions by ECOWAS countries and border closures, which complicate import and export activities. Pests and rapid population growth further exacerbate food security pressures.

Addressing these challenges requires training farmers in new methodologies and farming techniques to prevent soil erosion and manage rainfall variability. Implementing pluvial capture systems and adopting holistic natural resource management strategies can help tackle microclimate differences, improve soil management, and promote sustainable water resource practices.

Historical data from 1999 to 2012 indicates that rice is the highest-yielding crop per hectare at 2.54 tons/ha, followed by maize (1 ton/ha) and millet (0.4492 tons/ha). However, in terms of average annual production, millet leads significantly with 2.736 million metric tonnes.

As aforementioned in the first section, Niger suffered trade sanctions throughout 2023, which were only lifted in February 2024. These sanctions had a significant impact on the country’s economy, particularly affecting inflation rates. Inflation skyrocketed from 1.5% in January 2023 to 7.8% in September of the same year. The primary driver of these inflationary pressures was the surge in food prices, which remained high at around 10% in November and December 2023. The situation was exacerbated by ongoing security issues and terrorist attacks targeting both the civilian population and government infrastructure. These attacks disrupted livestock and crop production areas, resulting in lower food and animal supply, further driving up prices. This was particularly problematic in the Diffa area, which faced frequent security crises throughout the past year.

Additionally, a deficit in rainfall not only reduced crop yields but also led to a decrease in forage areas. Consequently, farmers were forced to rely on feed supplements for their animals, increasing their operational costs and reducing their purchasing power. As a result of these compounded challenges, livestock exports plummeted by 79.5% in Q3 2023 compared to the previous year. To safeguard these exports, military escorts were required to transport livestock to West African countries, aiming to maintain supply and stabilize prices.

Other factors contributing to the economic strain included the depreciation of the Nigerian naira, which led to reduced imports from Nigeria and altered demand patterns. Overall, 2023 was a year fraught with challenges for Niger. Labor demand was low due to decreased cultivation areas, and malnutrition cases soared to almost 1 million children under the age of five. The sanctions and insecurity also led to a shortage of food and pharmaceutical inputs. Consequently, food aid continues to be a critical lifeline. Agriculture inputs, such as fertilizers and seeds provided by the international community, remain key resources that save lives and offer temporary support to Niger’s struggling families.

I would like to briefly discuss the fertilizer market. Between 2021 and 2023, we witnessed a substantial increase in fertilizer prices. This market is influenced by various global trade disruptions, including supply chain interruptions and turnaround delays during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, geopolitical tensions significantly impact fertilizer prices. For instance, in 2023, China, a leading producer and exporter of fertilizers, blocked exports to secure its domestic supply. This action effectively removed one-third of ammonia and phosphates—both key fertilizer inputs—from the global market. Belarus, responsible for 20% of the global potash supply, faced international sanctions, and the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian conflict further disrupted fertilizer supplies, contributing to higher prices. Moreover, Russian natural gas, a critical component in ammonia production, experienced severe shortages, exacerbating price increases.

Other factors, such as adverse weather conditions (e.g., freezing temperatures or hurricanes), can disrupt natural gas production or lower nitrogen output, as seen in the U.S. in 2022. Fertilizer demand is closely tied to food demand; when farmers aim to boost supply and production yields, their increased demand for fertilizer, combined with supply shortages, drives prices upward. Price volatility remains a significant concern. For example, the price of urea fertilizer peaked at 925 USD/MT in April 2022 but dropped to 313 USD/MT by April 2023. Similarly, the cost of Diammonium phosphate (DAP) fell from 954 USD/MT per ton a year ago to 637 USD/MT today, and potassium chloride decreased from 1,200 USD/MT per ton to 408 USD/MT. The spike in fertilizer prices disproportionately impacts developing countries due to their heavy reliance on agricultural output.

Waste in Niamey (Niger)

A study conducted by Moussa et al. (2023), in collaboration with the Engineering University of Gandhinagar in India and the Technical University in Niger, examined waste management in Niamey, the capital of Niger. This research is noteworthy for future investigations and potential business initiatives aimed at addressing waste management issues and market gaps.

Niger, experiencing the highest population growth rate globally, faces significant challenges and opportunities. Annual waste production escalated from 264,444 tons in 2008 to 318,141 tons in 2012, with a collection rate of merely 47%. Niamey Urban Community stated that the citizens of Niamey produce 0.75 kg of waste per person per day. Consequently, over half of the city’s waste remains uncollected, accumulating in informal dumps in public areas and near residential zones. This situation not only has economic ramifications but also heightens health risks, fostering the spread of diseases such as malaria and cholera.

The primary issues stem from insufficient financial resources, a lack of technical expertise, and inadequately trained personnel within government authorities. Furthermore, the machinery and automation required for efficient waste collection are lacking, compounded by inadequate infrastructure, leading to poorly managed urbanization. The study focused on the Niamey I Communal District, one of the five communes in the Nigerien capital generating significant amounts of solid waste.

Effective waste management is a critical concern for urban areas, and the stages for waste management in Niger include pre-collection, collection, transport, and dumping. There are two primary methods of pre-collection: voluntary methods and door-to-door collection. Voluntary pre-collection involves residents using buckets, bins, or wheelbarrows to transport waste to a nearby collection area located within half a kilometer from their homes. The door-to-door collection is predominantly handled by the informal sector, utilizing rickshaws, animal-drawn carts, or human labor, organized by individual entrepreneurs, associations, or committees.

Once collected, waste is transferred to official City Council bins and then transported to old mines converted into landfills (quarries). However, these landfills are inadequate for handling waste, thereby creating environmental and health risks. This situation mirrors the waste management challenges faced by other African cities.

According to a survey conducted by researchers, 50% of households in the sampled population self-dispose of waste, 38% use informal pre-collection services, and 12% subscribe to private waste collection services. This indicates that about 88% of households rely on informal waste collectors or young family members for waste disposal. The decision to hire private services often depends on the household’s socio-economic status. Low-income households prefer informal operators due to lower costs, which range from 150 to 1 500 CFA francs per month, while upper-class households tend to hire private operators at an average cost of 2 000 CFA francs per month (USD 3.26 at June 2024 rates). Informal service providers operate without municipal authorization, whereas private operators are recognized by municipal authorities.

The cost of waste collection services varies significantly across different regions. In Niamey I, the costs are relatively low compared to other regions mentioned in the survey. Conversely, the Commune of Abomey Calavi, located in Benin, has higher waste collection fees ranging from 1 500 to 3 500 CFA francs per month, depending on the type of housing. The different housing types likely lead to varying amounts of waste produced, influencing the cost.

In Bamako, the capital of Mali, waste collection fees are higher than in Niamey I, ranging from 1500 to 3000 CFA francs per concession (a plot of land or housing unit). In gridded areas with organized urban layouts, the fees are even higher, with larger concessions producing more waste, leading to monthly costs of 4 000 to 5 000 CFA francs (for USD comparison purposes every 1 000 CFA is equivalent to 1.63 USD at today’s rate).

Reuse and recycling practices are present in Niamey through informal waste recovery systems. According to researchers, these systems categorize waste into metal, plastic, and cardboard. Metal items include cans and parts from motorcycles or cars, while plastic items consist primarily of water and juice bottles. Waste pickers are typically compensated per kilogram of collected waste, receiving an average of 200 CFA per kilogram for metal objects, 25 CFA per kilogram for plastics, and 15 CFA per kilogram for cardboard. These rates are generally higher compared to other cities in the region; for instance, Bangangté in Cameroon offers an average of 75 CFA per kilogram of metal, and the Niamey IV Communal district pays between 65-75 CFA per kilogram of metal collected.

Inadequate waste management practices and improper disposal disproportionately affect the poorest communities and nearby livestock. Vulnerable individuals often scavenge for items to resell or recycle, exposing themselves to injuries, contaminants, and toxic environments, particularly in unregulated, informal dumpsites. These sites lack oversight, allowing animals to consume toxins that then enter the human food chain.

Incineration is a common waste disposal method, yet it releases uncontrolled polluting smoke, exacerbating air pollution with harmful gas emissions such as methane, carbon dioxide, and chlorofluorocarbons, impacting nearby populations. Furthermore, the absence of sanitary and regulated landfill protocols leads to the creation of leachate, which infiltrates soil and contaminates water sources—resources that are already precious and scarce in Sub-Saharan regions.

There are many business opportunities in Niger for international companies that can accelerate the transition towards a more sustainable waste management system including:

- Training and development of personnel for waste processes;

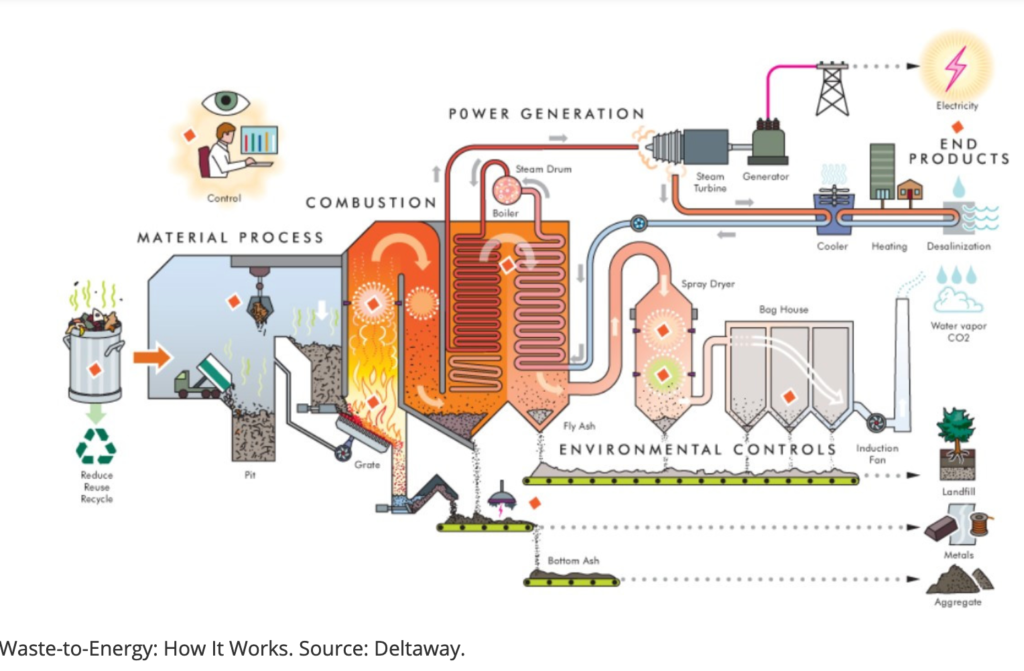

- Waste-to-energy plants that use household garbage as a fuel for generating power and electricity;

- Waste separation and plastic and metal recycling businesses for making other products;

- Packaging companies can create innovative products to store food in durable containers instead of plastic bags (around 90% of the food is packaged with plastic bags);

Bibliography

- World Bank. (2024). Overview of Niger.

- SARE. Guidelines for Intercropping.

- World Bank. (2024). Niger Overview.

- ProducePay. (2024). Factors Driving Fertilizer Price Spikes.

- ReliefWeb. (2024). Niger Food Security Outlook Update.

- Africapolis. (2020). Niger Country Report.

- Trading Economics. Mali Imports.

- Offshore Technology. (2024). Agadem Complex Conventional Oil Field.

- World Oil. (2024). Five Niger Oil Workers Held in Benin Over Crude Export Dispute.

- Coface. (2024). Country Risk Files: Niger.

- World Nuclear Association. Niger Country Profile.

- Trading Economics. Uranium Commodity Prices.

- ReliefWeb. (2020). Niger Population Density.

- World Nuclear Association. Nuclear Power in the World Today.

- Odyssey Energy Solutions. (2024). Remote Monitoring and Control Technology.

- ITU. (2017). Country Profile: Niger.

- CGS. (2017). Research Paper on Niger.

- ETH Zurich. (2011). Term Paper on Niger.

- S&P Global. (2024). Niger on Verge of First Oil Exports.

- USAID. (2024). Power Africa Initiative.

- Green Mini Grid. Introduction to Mini-Grids.

- USAID. (2024). Niger Power Africa.

- Geo-Ref. Niger Physical Geography.

- Quora. CDMA Technology in the EU and the US.

- ITU. (2017). Country Profile: Niger.

- Developing Telecoms. (2020). Telecom Regulation in Niger.

- Africa Container Shipping. Top 10 Ports in Africa.

- Resilient Digital Africa. (2024). Telecom Operators in Africa.

- Britannica. Niger.