During my time at the European Investment Bank (EIB), I worked within the Restructuring and Resolutions Directorate, where I managed the repayment strategies of debtors facing financial distress. The EIB operates by borrowing funds from capital markets and lending them on favorable terms to projects that align with EU objectives. Its primary funding currencies are EUR and USD, with large bond issuances typically ranging between EUR 3-5 billion. These bonds come with diverse maturities, spanning from 2 to 30 years, and are issued regularly—at least six times per year—with robust dealer support to ensure a strong secondary market presence.

When bonds are issued, there are two key markets to consider: the primary market, where the bonds are initially sold, and the secondary market, where they are traded after issuance. For supranational institutions like the EIB, maintaining liquidity in their bonds is crucial. High liquidity keeps bid-ask spreads narrow (more on that later) and increases investor confidence, as it ensures bonds can be easily resold. This is similar to buying a house in a high-demand area—reselling it is much easier compared to a property in a less desirable location.

The EIB has been investing in energy projects since the very beginning, adapting its focus to meet the changing needs of the energy sector and the broader goals of the EU. An Energy Evaluation Report took a closer look at energy-related lending in the EU and found that it dropped from 18% of total lending in 1990-1995 to just 12% between 1996-2000. Interestingly, 94% of these energy loans were individual ones, funding 331 major projects and programs.

During that time, most of the funding went to power stations (24%), including Combined Heat and Power (CHP) plants, followed by electricity grids (21%), gas grids (19%), renewable energy (11%), oil and gas fields (11%), and refinery investments (6%). With the EU energy markets gradually deregulating, it seems there was more pressure to keep costs and project timelines under control.

Environmental factors have become a big deal in project planning and execution. In fact, some projects made changes to their designs to reduce environmental impact. While this often meant higher costs, serious technical or operational challenges were super rare—only two cases were reported in the projects analyzed.

When it comes to project finance, commodity price fluctuations are a huge deal. That’s why many people think of project finance as a form of risk-sharing. Risk is always part of the game—it just needs to be managed so the potential upside outweighs the downside. Insurance can help, but it just shifts the risk from one party to another. What really matters is solid planning, scenario analysis, and figuring out how sensitive a project is to different situations. You’ve got to understand how things could play out, even in extreme cases (remember when oil prices went negative during COVID-19?). It’s critical to know how well a project can hold up and at what point it stops making sense.

Since the mid-80s, gas had become a favorite due to its lower costs and smaller environmental footprint. This shift had a big impact on EIB-financed projects. Gas networks and gas-fired power plants often outperformed expectations, delivering cheaper electricity compared to options like coal. On the flip side, oil and gas field projects and coal power stations didn’t do as well as planned. Lower oil and gas prices, combined with the rise of gas as a more competitive option, were major factors behind their underperformance.

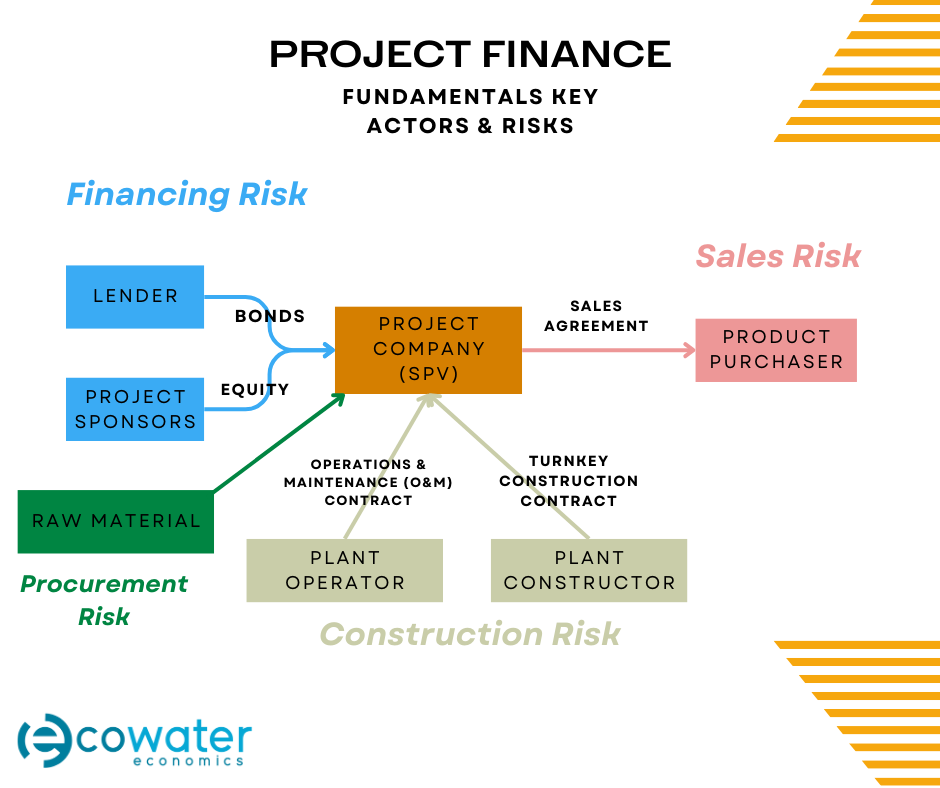

To understand what makes project finance unique, we must first explore its key characteristics. At its core, project finance begins with an investment idea. The project sponsor—typically the driving force behind the initiative—creates a separate legal entity known as a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) by injecting equity. This sponsor can act alone or collaborate with others in a joint venture.

Project sponsors often have a deep connection to the project, as it may represent a critical element of their broader business strategy. For example, a power company might establish a legally independent cogeneration plant to supply steam and power to a stable group of customers. These customers, referred to as “Purchasers,” can vary widely—they might be independent companies, public institutions, or even another subsidiary of the original project sponsor.

A defining feature of project finance is that a single party can play multiple roles. The more ties a sponsor has to the SPV, the more revenue streams it can potentially secure. For instance, if a Cargill subsidiary provides equity for an SPV and another Cargill entity commits to purchasing its output, the transaction carries significantly lower risk. This is because the financial stability of the purchaser is already well-established, unlike dealing with a group of buyers whose creditworthiness might be uncertain.

Purchasers can generally be classified into two main categories. The first category is referred to as **offtakers**—buyers who commit to purchasing the entire output of a company. These wholesale agreements provide projects with financial stability by ensuring predictable future cash flows. Offtake contracts, especially long-term ones like 25-year take-or-pay agreements, are highly valued by lenders. Under such agreements, if the buyer fails to consume the plant’s output (e.g., energy), they must pay a penalty fee, further securing the project’s revenue.

The second category includes generic buyers, where it is impossible to identify specific purchasers or predict their buying patterns. However, on an aggregate level, demand can be more reliably forecasted. Examples include toll roads or parking lots—while exact user numbers cannot be guaranteed, projections can still guide revenue estimates. Unlike wholesale contracts, these arrangements are less reassuring to lenders due to their inherent unpredictability.

In project finance, Operations & Maintenance (O&M) agreements also play a crucial role. These contracts obligate a company to maintain and service the plant (or SPV) under strict quality standards set by qualified engineers. Failure to meet key performance metrics can result in penalties. Typically, O&M agreements are long-term and may be transferred to the project sponsor after the construction phase is completed.

Another critical player in the process is the contractor under the turnkey construction contract. Often referred to as the Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) contractor, this entity—or consortium—is responsible for designing, building, and delivering the project. The EPC contractor must adhere to detailed technical specifications and ensure the output meets or exceeds minimum performance standards, such as energy production, emissions levels, failure rates, or heat rates. Bonuses may be awarded for exceeding efficiency thresholds or completing the project ahead of schedule, incentivizing high-quality performance and timely delivery.

Together, these key contracts and players form the backbone of successful project execution, ensuring efficiency and financial security across all stages.

In our next post, we’ll dive deep into project finance theory, exploring essential concepts like the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), Return on Investment (ROI), volatility, and correlations. These key definitions are fundamental for anyone aspiring to build a career in finance.