Twenty years ago, before I left my hometown in Mexico, there were only two roads connecting us to Mexico City—a toll road and a free road. To reach nearby villages, drivers had to take long detours that eventually led to one of these routes. This situation reflects a broader issue in many Latin American economies, where road networks were designed primarily to link small towns and villages to capital cities. Unfortunately, little attention was given to interconnecting these smaller towns, which could have fostered economic growth within regional areas. But how can such large-scale investments be realized?

In project finance (PF), sponsors play a pivotal role in driving infrastructure development. Sponsors can be classified into four main categories based on their core business models or objectives: industrial, public, contractor/developer, and financial. Before embarking on a large-scale project, sponsors must have a clear vision and a meaningful connection to the initiative.

To better understand these dynamics, let’s examine a recent undertaking partially financed by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD): “Project Neptune.” This project focused on developing, constructing, and operating a 1.5 GW offshore wind farm in the Baltic Sea.

The sponsors behind this initiative are Polska Grupa Energetyczna S.A. (PGE) and Ørsted A/S. PGE, Poland’s largest vertically integrated power utility, has a market capitalization of EUR 3.6 billion (as of October 2024) and operates primarily in Eastern and Central Poland. Its activities span conventional and renewable energy generation, district heating, railway energy services, and electricity distribution and supply. PGE is predominantly state-owned (60.86%) and listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange.

Ørsted A/S, a global leader in wind power development, is also majority state-owned, with 50.1% of its shares held by the Danish government and a market capitalization of EUR 24.5 billion. Ørsted commands a 25% share of the global offshore wind market and specializes in the development, construction, and operation of offshore and onshore wind farms, solar farms, energy storage systems, and bioenergy plants.

Both PGE and Ørsted are unique in that they function as both public and industrial sponsors. Their state ownership aligns with public interest, while their operational expertise positions them as industrial leaders. Moreover, their business models enable seamless integration with the project’s output. For instance, PGE can purchase the energy generated by the offshore wind farm to power the Polish regions it serves.

From a project finance perspective, sponsors typically have a strategic stake in their investments, often becoming long-term suppliers or buyers of the project’s output. This relationship makes them ideal candidates for such ventures. To succeed, sponsors require high levels of operational and technical expertise. Additionally, fostering strong customer relationships and accurately forecasting market growth are critical to ensuring stable revenue streams.

A special purpose vehicle (SPV), named Elektrownia Wiatrowa Baltica-2 Sp. z o.o. (referred to as the “Project Company”), was established through a 50-50 joint ownership by both sponsors to bring the project to life.

Beyond energy generation, governments often pursue broader social or environmental objectives when engaging in project finance (PF). In the case of Project Neptune, EU governments aim to:

- Accelerate the transition to renewable energy and advance decarbonization efforts,

- Strengthen Poland’s investment climate by supporting innovative, higher-risk energy projects that might otherwise be overlooked by risk-averse investors, and

- Enhance Poland’s long-term energy security policies.

I will provide more detail later on how long-term energy security is ensured. For now, consider that PGE has arranged a 25-year contract with the SPV, under which the SPV agrees to supply electricity to PGE at a fixed price. To account for fluctuations in electricity spot prices over this period, the Polish government steps in to cover any price differences, ensuring:

- PGE faces minimal supply risk due to the fixed price structure of the 25-year agreement, and

- The SPV enjoys stable, predictable cash flow over the contract term, giving lenders the confidence to invest in the project.

With this real-world PF example in mind, let’s explore the different types of public-private partnerships (PPPs) that exist.

Collin and Hanson (2000) define PPPs as agreements between a public body and one or more private firms, where all parties share risks and rewards through joint ownership of an initiative. For instance, private companies can construct hospitals or schools, which are then funded by public entities and used by the general population (referred to as users).

Another common form of PPP is toll road agreements. In these cases, private companies are contracted to build, operate, and maintain toll roads. Through concession agreements, they are granted the right to charge users for road access. Metrics like Annual Average Daily Traffic (AADT) are critical for evaluating project profitability, forecasting earnings, and determining break-even points. Toll roads connecting major cities, industrial hubs, or airports typically offer higher revenue potential for private concession holders. Other examples of concession-based PPPs include cell phone networks, water supply systems, and sewage treatment plants.

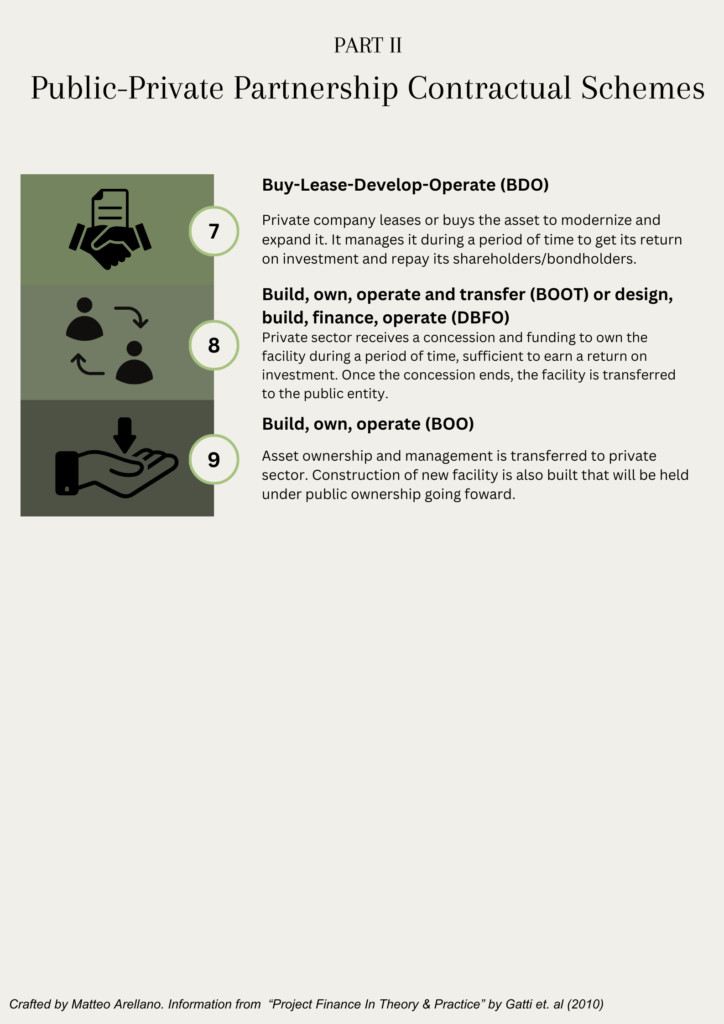

The structure of a PPP varies depending on factors such as the level of risk borne by the private partner, the financing required, and the governance model. These considerations lead to different contractual frameworks, as outlined by Gatti (2012).

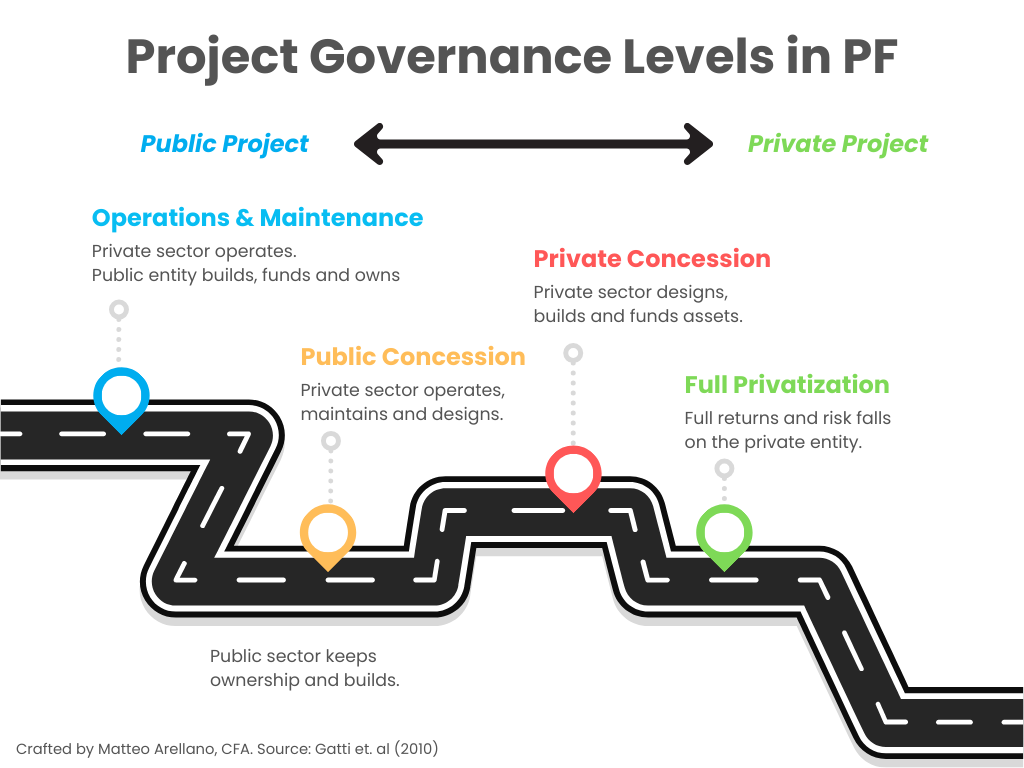

Project governance shows the degree to which a project is mostly public or private. When a private entity only operates an asset without getting involved in the design, build up or financing process, we say that this is predominantly public PF. On the other hand, when a private company (or consortium) designs, builds, and maintains ownership of the asset, this is considered private PF. In the image below, you can see the different types of PF according to the level of public-private responsibilities and risks assigned.

In this section we have learned a lot of new concepts. We started talking about the strategic goals that sponsors might have when deciding to set up a PF SPV company. These include vertical or horizontal integration, cashflow stability and revenue potential gains as well as guaranteeing public wellbeing or meeting important energy (or water) needs for the respective governments or parties. Public-private partnerships play a key role in determining the risks and responsibilities shared by each stakeholder. The bigger the responsibility, the higher returns expected. Whenever there is more private involvement, it is considered a more private PF project, whereas if the public body performs most of the tasks, including, design, build and fund the asset, it is known to be closer to a real public PF project. Private companies might get involved due to their expertise, technological know-how and funding possibilities.

Brief Comment About Economic and Political Forecasts

Project finance often involves large-scale companies managing diverse product portfolios. A notable example is Ørsted, the Danish offshore wind giant, which, as of February 2025, faces impairment losses in its US-focused investment infrastructure portfolio. While multiple factors could contribute to this, a lack of political support and rising tariffs on foreign companies in the US may pose significant risks to existing projects and new greenfield investments.

In response to mounting challenges such as higher costs and supply chain disruptions, Ørsted has announced a 25% reduction in its 2030 investment program. Political shifts and trade tensions play a critical role in shaping renewable project finance models. For instance, sourcing components from tariff-heavy regions like China, amidst escalating trade disputes with the US, can drive up costs and erode economic competitiveness. According to Reuters, Ørsted’s 2024-2030 investment target has been downgraded from an initial 270 billion Danish kroner to a revised range of 210-230 billion kroner.

Join me to learn project finance, data analysis and financial modelling on 1-on-1 sessions! 30 minutes private session for FREE.